Introduction

“I just find it, you know, really, really hard to concentrate. Because of all the horrors, you know, we perceived.”

— Student in Breaking Bad, requesting A’s for everyone

“I’m not afraid of death. What could death bring that I haven’t faced? I’ve lived. Life is the worst.”

— Side character in Better Call Saul

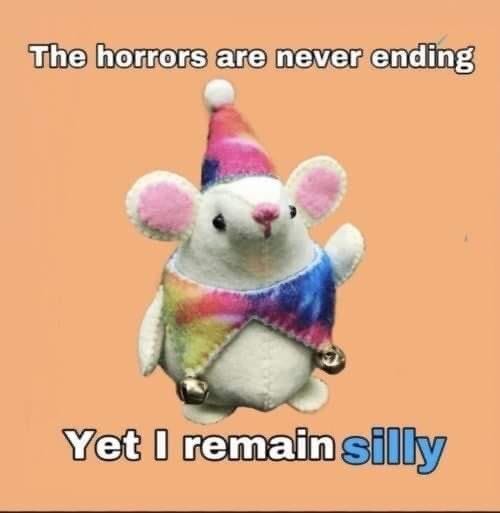

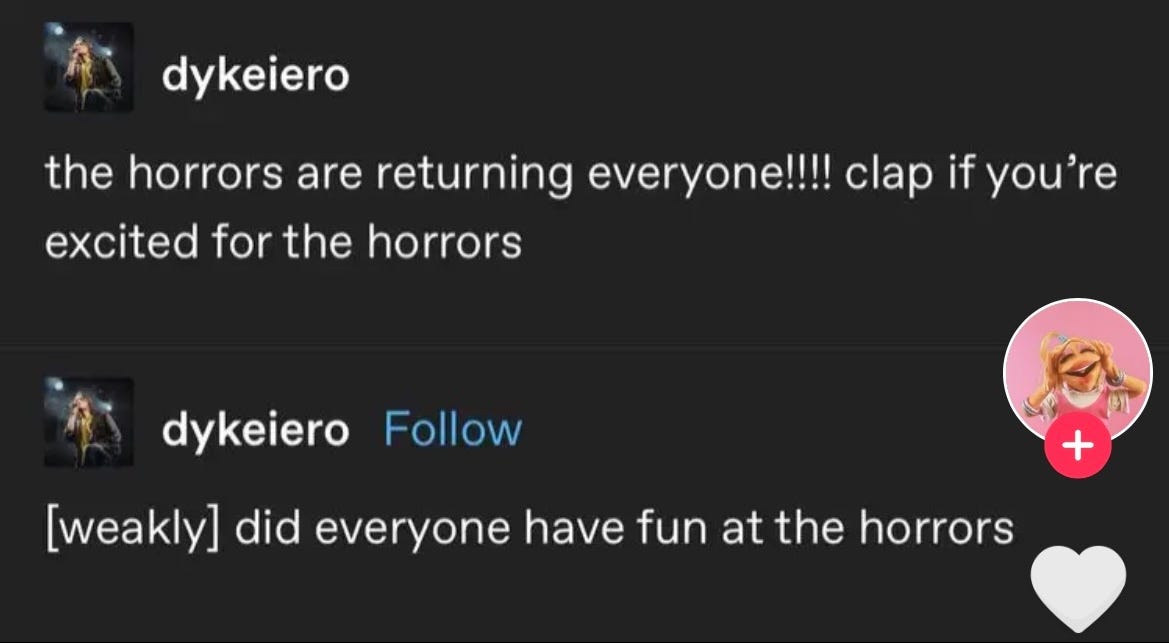

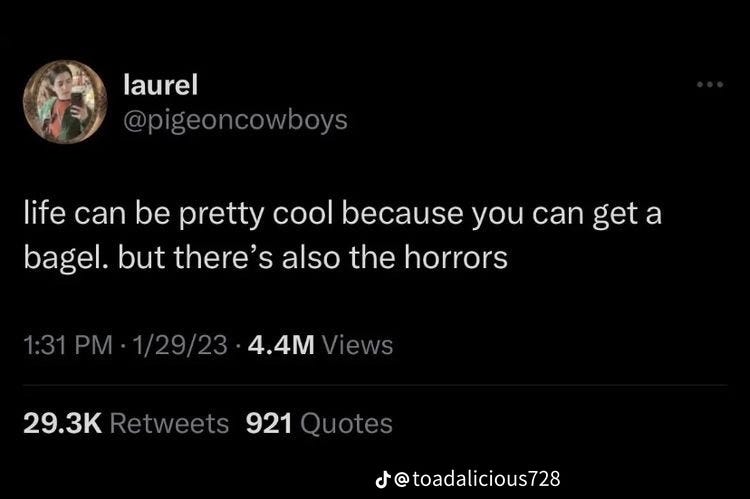

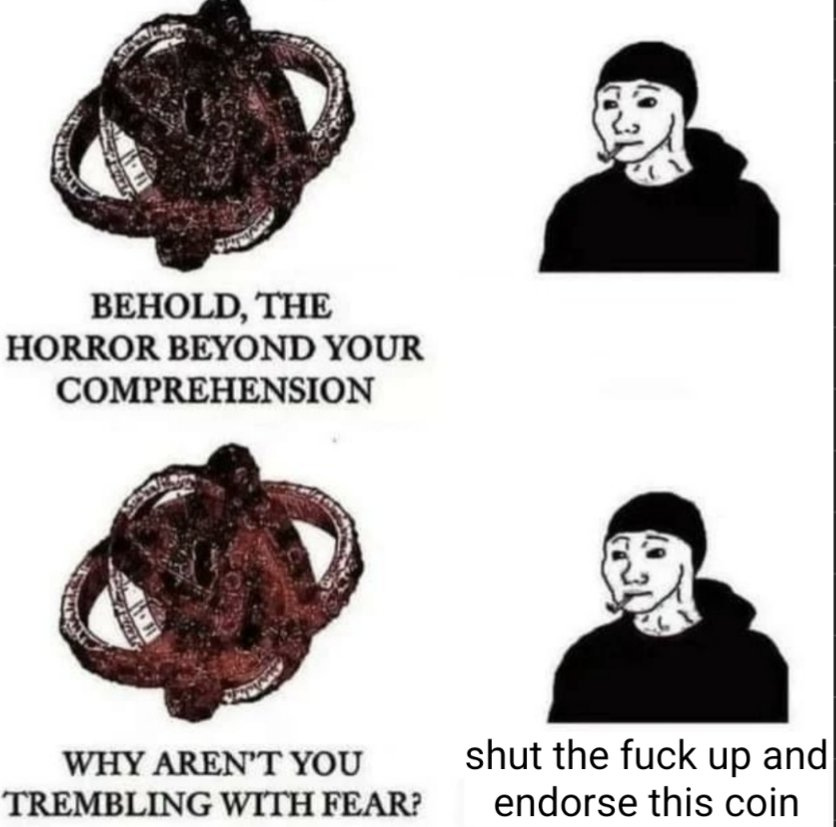

If you’re anywhere near my corner of the internet, you may have encountered some glib references to “The Horrors.” For example,

(See the Appendix for more examples.)

So what’s this all about? What are these so-called horrors, why are they beyond comprehension, and why are they often contrasted with delectable treats?

A few months ago, some friends discussed a curious topic. If I recall, I prompted the conversation with a favorite question: “To what extent have you processed the fact that you are going to die?” To my surprise, two friends agreed that it doesn’t really matter because “death isn’t scary; it’s life that’s scary.” I pressed: surely scary events occur in life, but even at rock bottom—death of friends, estrangement from family, homelessness—you would still rather live than die, no? I did not receive a satisfying answer to this question, but both maintained their conviction. In the subsequent months, I have sought to remain sensitive to this perspective, and—for better or worse—this attitude has borne fruit. I learned early that I must forgive my teammates their reticence; words often escape the Horrors (more on this below).

I have also seen further confirmation of their perspective, for example, a Facebook post on a meme page, claiming, “The truth is, living is more terrifying than death, for every moment you’re alive is another moment where you could be subjected to the worst tortures of existence . . .” Or this meme, which testifies that “the living envy the dead:”

The expression that suicide is the coward’s way out also encodes this sentiment.

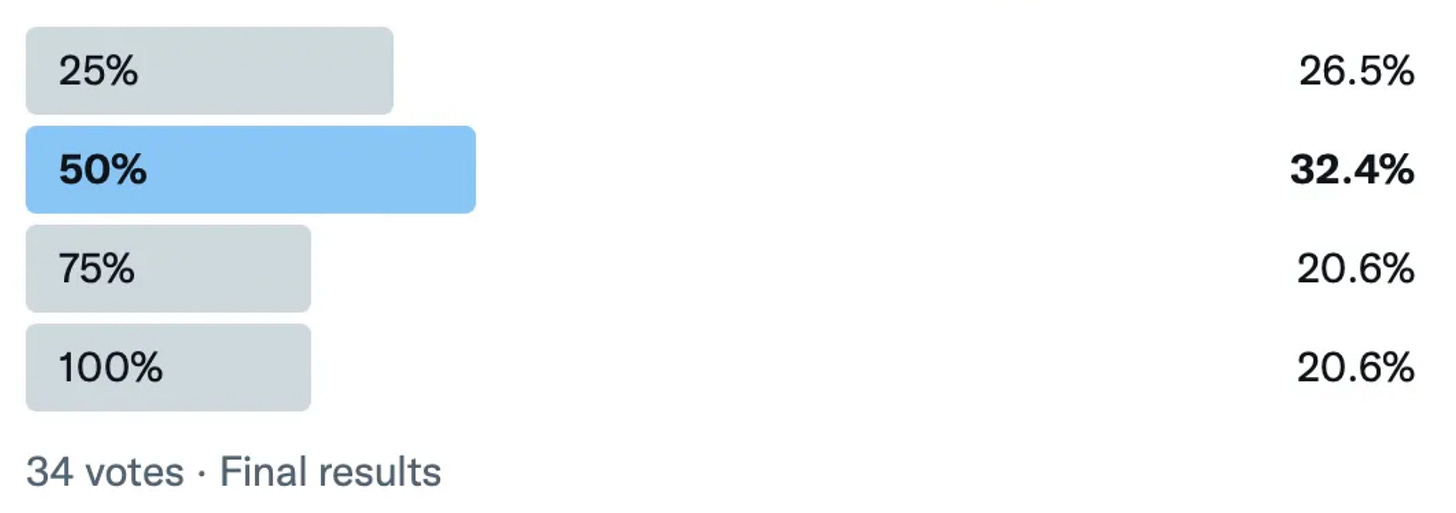

The Horrors have come to define the latest chapter in my life, providing a frame with which many of my experiences enter into relation.1 I peppered my last two posts with quotes and lyrics to testify to the prevalence of their motivating sentiments. With respect to the Horrors, I can appeal to cold, hard data. I ran a twitter poll asking which is scarier:

The numbers don’t lie! Okay, maybe they do (n=20), and who knows why people voted the way they did, but it does seem like some common cause unites these 11 people and my two friends. Bewildered, I appealed to this antinatalist manifesto, but I found no sympathy for the position. And their whole schtick is that life is bad! So I hope that if you get nothing else out of this post, at least you might find some solace in commiseration.

Terminology

“I suspect that spookiness is a lot like love, in the sense that everyone experiences it in a way that seems so private, so specific, that they believe nobody else feels it quite like they do.”

— Eliza Brooke, “On Spookiness”

So, what do I mean by “horrors”? Why not “the terrors” or “the darkness” or “the omnipresent evil of the universe”? The honest answer is that the term originated with the first comic above and then it stuck. You can call it whatever you want, but the feeling I’m speaking to possesses these properties:

Scary

Uncertain

Existential

I elaborate on uncertainty in the following section. The Horrors are existential in the sense that they follow from existence; they inhere to the human condition (or at least your subjective experience of it). This quality distinguishes the Horrors from garden-variety anxieties like “All my friends hate me,” which are the product of particular circumstances. Certainly, we can find edge cases: what if you are afraid that your house is haunted? In some sense the fear is escapable because you could simply move out, but maybe it’s more immutable if you’re scared of the existence of ghosts. Ultimately, I’m not in the business of adjudicating whether a particular fear qualifies as a Horror. For me, Relationship Skepticism satisfies the above criteria.

Unspeakably Sad

“Words are futile devices.”

— Sufjan Stevens

As a blanket caveat, I think language fails to adequately capture the nature and depth of the Horrors: hence the opacity of the memes we started with. I will suggest some possible horrors, that one may resonate with you, or that the examples might establish a profile against which you can identify your own idiosyncratic horrors. But even my examples often defy verbalization.

In general, when we’re scared, we tend to clam up, so we would expect the Horrors to be difficult to talk about. But for some Horrors, we can further identify specific reasons why words may fail them, and insofar as I can point to such explanations, I strive to do so. On the other hand, you may have an abiding sense of the Horrors—a sense that there’s some “there there”—and remain perplexed as to the source of their ineffability. As if your mind is an instrument too blunt to register their subtleties.

Fortunately, there is precedent for analyzing such a seemingly intractable domain. Consider silence. An impoverished definition is “the absence of noise,” but this doesn’t do justice to the meaning of silence, as I understand it. Instead, we can turn to social attitudes toward silence, confronting the awkwardness and tension to which people go great lengths to avoid, and reconciling the peace and serenity that offer a countervailing attraction.

Similarly, I have recently come to believe that seriousness is not a personality trait unto itself, but is instead the absence of humor. Yet this definition struggles to convey what I mean when I call someone “a serious person,” which is not a negative statement about a deficiency, but is instead a positive statement about a disposition. As with silence, we can better understand the meaning of seriousness by zooming out a level to focus on the attitudes toward seriousness, which tell us a great deal about the object itself. I think the same is true of the Horrors: like a sun that forbids direct observation, we can still learn their nature by the shadows they cast.

In the sciences, this technique has good company. For example, we knew that black holes existed before observing one directly by the cosmic behavior they would explain. To take another example, I’m told that we have not identified the mechanism behind aging, but we understand attributes of the mechanism through observations about natural selection. Birds, who face less predation than mammals, also enjoy longer lifespans. When a natural event isolates two communities of the same species, the community that faces weaker selection pressures will develop longer lifespans. From this sort of evidence, biologists conclude that aging is related to the way energy facilitates rapid reproduction.

This podcast extends similar reasoning to consciousness and religion: despite its mysteries, we can understand consciousness itself by focusing on meta-consciousness, our awareness of our awareness. Likewise, we can learn about God by focusing on our attitudes toward God. Indeed, according to a past professor, one of the three primary questions that occupy theologians is “How do we speak of God?”2 If God is precisely that which is beyond human comprehension, how can we direct our language at that entity? All of this is to say that we are not in uncharted territory when we grapple with the uncertainty of the Horrors.

Life: Gift or Curse?

“Life was a jail, and we found the key.”

— Midnight Gospel, “It Feels Good to Be a Zombie”

As a first pass at gesturing toward the Horrors, consider the following thought experiment, courtesy of Wait But Why:

How Long Would You Live if You Could Choose ANY Number of Years?

Here’s how it works. You wake up and find yourself alone in a room. The only things in the room are a table, a chair, a calculator, and a note. The note says:

You have exactly 10 minutes to choose how many years you want to live and type the number into the calculator. At the end of the 10 minutes, you’ll be escorted out of the room, and your decision is permanent and unable to ever be changed. You’ll live for exactly that many years and then you’ll die. Oh also…every other human on Earth is currently in a room just like this making the same exact decision and you won’t know what they chose until you leave the room. If you enter no number into the calculator, your life will go on exactly as it had before, unaffected — you’ll die a natural death whenever you would have if this had never happened.

Other information in the note’s fine print:

There’s an infinity button on the calculator, and there are endless digit spots.

(Some caveats follow, along with Tim’s answer, which illuminates some strategic considerations.) I raise this problem because I find that many respondents hold the combination of beliefs:

Life is good!

I would not hit the infinity button. Maybe I would spam 99999999… for 10 minutes, but the resulting lifetime would be unimaginably shorter than if I’d hit ∞.

I feel like there is some tension here that demands resolution by an account of why quality of life asymptotically deteriorates. Here are some candidate explanations:

What if I’m the only person in the world that presses infinity! I will witness the death of everyone I love and eventually survive everyone else, becoming the lone inhabitant of a barren cosmos.

I would get bored. As Anders Sandberg notes, with infinite time, you would eventually read every book, even if the pile of new books was growing at a “faster and faster and faster rate.”

What if I came to decide that life was bad! And then I were trapped as if in an eternal bad trip, perpetually subject to the torture of existence! I don’t know why this would occur, but the fear of fear itself is sufficient to stay my hand. Analogously, some people avoid tattoos out of fear of regretting their permanent mistake.

Number 3 is my preferred explanation (though I would perhaps elect for ∞ anyway), but I think any of these might constitute a Horror: scary, uncertain, and existential. In fact, I’ll elaborate on loneliness below. I think many people would offer an alternative justification for their finite entry in the calculator; this exercise serves as a divining rod that may lead you to the Horrors flowing deep under your own psyche. Can you imagine feeling like life is a curse? Like you have to endure every day in a condition you never invited? Like God handed you a life sentence at birth? Horrors abound!

Caviola et al 2021 reveals a similar discrepancy in beliefs about quality of life.3 Among respondents in the US,

16% said their life to date has not “involved more happiness than suffering.”

31% would not choose to “live the exact same life again from the beginning (without remembering anything from before, so experiencing everything as if for the first time).”

If life is so good, why not live it again? Maybe the Horrors bridge some of this gap.

Horror 1: Mortality?

“First, we’re born, and then we die, and in between, most of us spend all the time crying.”

— Midnight Gospel, “It Feels Good to Be a Zombie”

“We cannot look squarely at either death or the sun.”

— Francois de La Rochefoucauld

The obvious suspect in conversations about existential dread is death. People have tried various measures to internalize their own mortality, from whispering “memento mori” to placing a human skull on their desks to receiving app notifications five times a day. And yet, when asked to what degree people have come to terms with the fact that they will die, we see results like:

One reason for the collective lack of processing is that death sucks (even if it’s not as scary as life), and so does thinking about it.

Another, more insidious reason comes down to what I’ll call “public semiotics”—the meanings that we make out of public structures and rituals. I have the impression that our present social arrangements betray an almost conspiratorial commitment to occluding death by insisting everywhere on life. Not only is discussion of death taboo, even our physical practices have evolved to preclude contact with deceased family members.4

More subtly, at the grocery store you encounter rows of fresh produce; at the first hint of rot—BAM! It’s garbo time. And when a tree dies in a residential area? Timber! Fences and bushes immure those uncommon cemeteries that luck into central locations, where even the determined mourner discovers green grass and fresh flowers. Departments of transportation collect roadkill from our highways, which trees often border to obscure the clear-cut fields immediately beyond.

Expanding on this highway dynamic, Antoine de Saint-Exupery writes in Wind, Sand and Stars,

“The airplane has unveiled for us the true face of the earth. For centuries, highways had been deceiving us . . . Roads avoid the barren lands, the rocks, the sands . . . Thus, led astray by the divagations of roads, as by other indulgent fictions, having in the course of our travels skirted so many well-watered lands, so many orchards, so many meadows, we have from the beginning of time embellished the picture of our prison. We have elected to believe that our planet was merciful and fruitful. But a cruel light has blazed, and our sight has been sharpened . . . we discover the essential foundation, the fundament of rock and sand and salt in which here and there and from time to time life like a little moss in the crevices of ruins has risked its precarious existence.”

William Shatner seemed to have a similar revelation during a “suborbital space tourism flight.” He reported that “Everything I had expected to see was wrong.” Instead of a beautiful, flourishing planet, “I saw a cold, dark, black emptiness. It was unlike any blackness you can see or feel on Earth. It was deep, enveloping, all-encompassing.” He concludes, “All I saw was death.”

I guess Interstellar hadn’t prepared him! Huh! Maybe when Hollywood does decide to portray death, their incentives are to capitalize on saccharine grief? Crazy stuff, bro.

In an earlier novel, de Saint-Exupery notes that our perspective on death emerges from a more private structure, as well: the home.

“[W]hat she would not have was this assurance of longevity. Those objects, she thought, lasted longer than I. They welcomed me, escorted me through life, and would one day keep vigil over my remains. But now I am going to outlive the things around me . . . Her house was a ship, carrying generations from one side to the other. The crossing makes no sense, neither here nor anywhere else, but what security there is in having one’s ticket, one’s cabin, and one’s bright leather suitcases.”

Even your antique tchotchkes might color your understanding of death, lulling you into an illusion of immortality.

I think fear of death often manifests as discomfort with impermanence. We trick out our cities with timeless statues and buildings that emulate ancient Greek architecture. More personally, my fourth grade teacher Mrs. Mengele once lured the class into molding pencil-holders out of clay before commanding us to crush them into oblivion. We comfort in the vague sense that our photos will stand the test of time. When I think of an interesting idea, or a punchy line, or a catchy guitar riff, my first impulse is to record it. And when we do part, we expect goodbyes and closure.

I was perplexed the first time I heard Sufjan Stevens profess, “I would rather be a flower than the ocean” because who wants to be a stupid flower? They’re briefly beautiful, then they disappear. Ah, but the ocean isn’t eternal, either! The pursuit of permanence is a losing game, and once you’ve excised your commitment to it, you can revel in the glory of flowerdom. Lord, make me a mayfly!

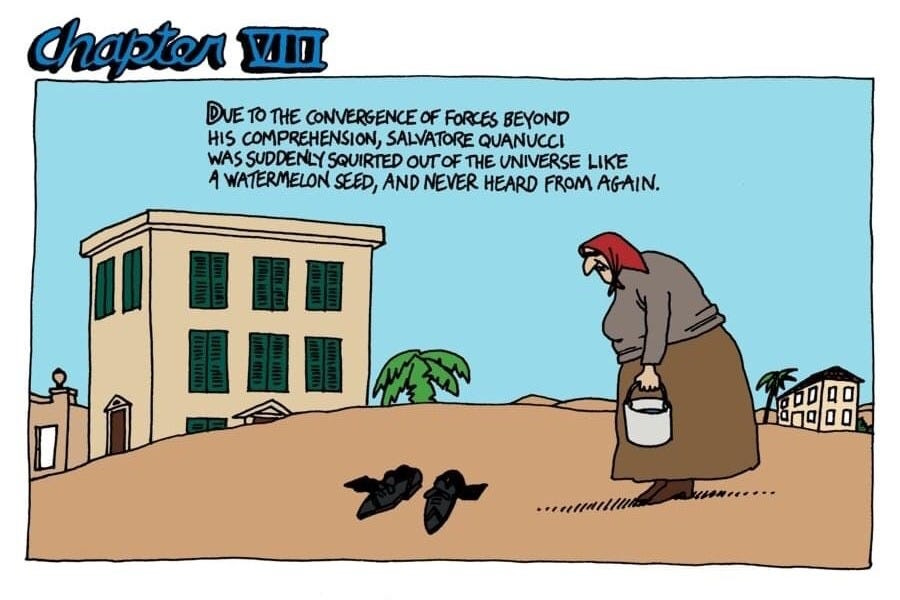

Like our friend Sufjan, I think you can take steps to unlearn permanence. You could buy a disposable camera but no film. You can burn your journals or compose a song with friends just to perform once for yourselves.5 Write in the sand or cook beautiful dishes or draw with chalk or carve ice sculptures. You can practice Irish goodbyes or get on this based stuff:

Mono no aware: literally “the pathos of things”, and also translated as “an empathy toward things”, or “a sensitivity to ephemera”, is a Japanese idiom for the awareness of impermanence, or transience of things, and both a transient gentle sadness (or wistfulness) at their passing as well as a longer, deeper gentle sadness about this state being the reality of life.

We take cues from our environment, and with respect to death, our social environment exudes the impression that death is rare, inappropriate, and strictly corporeal. When it does receive public attention, our media cloaks death in glory, renders grief a temporary Hallmark affliction, and assures that our reputations/projects/lineage will endure for posterity.

I’m sure there is no shortage of available means to disabuse yourself of these perverse distortions. If you’re concerned about romanticizing death, you might look into the case of R. Budd Dwyer, a Pennsylvania politician who shot himself in the head at a press conference in 1987. You can even find the disturbing footage. He had prepared to end on these remarks:

“I am going to die in office in an effort to ‘ … see if the shame[-ful] facts, spread out in all their shame, will not burn through our civic shamelessness and set fire to American pride.’ Please tell my story on every radio and television station and in every newspaper and magazine in the U.S. . . . Please make sure that the sacrifice of my life is not in vain.”

But you’ve never heard of this guy. Time and tide…

Death isn’t really a big horror for me because it falls short on the uncertainty dimension. I think I have a pretty good guess at what death feels like (“dreamless sleep,” etc). It’s scary and existential, but so was skydiving for me. Death is like jumping out of a plane, but one hundred billion people did it before you.

Horror 2: Loneliness?

“There ain’t nothin’ I fear so much as being alone.”

— Justin Townes Earle, “Yuma”

I have lots to say about the Impossibility of Truly Knowing and Being Known (shoutout RelSkep), but I’m going to try to restrict myself to the elements that are relevant to the Horrors.

Maybe you will be alone forever—maybe in the sense that you never find love, or worse, that you find love but you’re still alone! Party of one! The protagonist in John Green’s Paper Towns learns the painful lesson that the “windows” into his manic pixie dream girl’s True Self were in fact “mirrors” reflecting himself. (The girl’s name was Spiegelman, German for “mirror-maker.” John, you cheeky bastard.)6

Why might it be difficult to talk about loneliness? First, like death, it’s uncomfortable, stigmatized, and receives poor media representation. We even see a similar sampling bias: dead lonely men tell no tales. Second, what even is it? Something about being alone? If you google around, you will come across claims that loneliness is a composite of many different negative emotions. I don’t know why we suffer from such limited introspective access, but some of the difficulty seems to inhere to the emotion itself, rather than deriving from the first set of explanations.

Third, human connection is a necessary condition for the development of language. That is, community comes first, and communication follows. But the whole point is that lonely people are longing for human connection! Loneliness precludes the interactions that would occasion inventing better language for loneliness. If I’m wearing a straightjacket, I can’t shake your hand.

Horror 3: Evolution?

“There’s something powerful about looking at people and seeing the angels that never had a shot at heaven—though I prefer to see not angels, but monkeys who struggle to convince themselves that they’re comfortable in a strange civilization, so different from the ancestral savanna where their minds were forged.”

— Nate Soares, “Replacing Guilt”

There’s this moment at 11:50 of the Midnight Gospel episode “Vulture with Honor” when a novel species of pie-creatures emerges from a machine and crawls outside. One specimen encounters its own reflection, whom it threatens, before breaking down in tears. I think there are lots of ways to interpret the scene, but I take it to illustrate the creature’s discomfort with its physical existence. It confronts, for the first time, the question “What kind of a creature am I?”, and it doesn’t relish the answer.

There are some facts that I knew for a long time but spared careful examination. Humans are animals! I don’t know how many times I’ve made the point or specified “non-human animals” in discussing factory farming etc. Biochemical rules govern the cells that compose our brains and bodies. Human cognition displays some advantages and other disadvantages. There might be aliens.

But I didn’t internalize these ideas; I maintained peace of mind by compartmentalizing. Specifically, I used a teleological frame: I would start with my own existence, and then consider these facts relative to that anchor. But from the point of view of the universe, the situation looks very different: these facts came first, and I was an afterthought.

I am an accident of evolution, a byproduct of nature. Animals fought and reproduced and now I’m here. We are just one species among many: we outcompeted the others in our genus, and if humanity goes extinct, smarter beings might take our place. We would look as weird to aliens as they’d look to us. I am made of cells; my most intimate thoughts run on ancient hardware designed by evolutionary guess-and-check. At least I can cast some of this as serving my survival, thanks to natural selection, but once we add sexual selection into the mix, it goes all Costa Rica. Maybe I’ve appreciated the most meaningful and beautiful moments in my life only because our ancestors started getting the hots for others who appreciated similar beauty and meaning.

These ideas make me feel unwhole. Unsettled. Creaturely. Like I’m not at home in my own skin.

Take food, for example. Consumption is a necessity that binds every one of us; we have no say in it. Hunger is a reminder of our powerlessness in the face of evolution. But how do we respond? We valorize food! We profess our love for it, we spend time making it, and we entertain ourselves by watching others make it. We delight in identifying our “favorite” foods. We invented the institution of Michelin stars to award those chefs who spent their lives concocting food that tastes better than other food, so you and your lover can spend money on a romantic moment over a bowl of mortality. In this light, our relationship with food evokes Stockholm Syndrome: We couldn’t free ourselves from the chains, so we insisted on worshipping the chain-oil. Something something normativity. I think you could work through a similar thought experiment with sex.

Why don’t we talk about it? As with loneliness, I really don’t know what it is. The evolutionary heebie-jeebies? I just know it makes me shiver and tremble. But this Horror strikes me as more unusual than the previous two, so it’s not surprising that we lack adequate language. The question becomes “Why don’t people think about it?”, to which I’ll suggest some possibilities. First, science is confusing. Complacency or thanking God for specially making you are two moves that keep your selfhood intact. Second, compartmentalizing is easy and de-centering yourself is hard! That’s why sonder is such a big deal. Third, even if you understand the science and its bearing on your life, maybe you remain unperturbed! (If this is you, teach me your ways, for the love of God).

Little Shop of Horrors

“I’m afraid of the way that I live my life, I’m afraid of the way I don’t. I’m afraid of the things that I wanna do but I won’t.”

— AJJ, “Big Bird”

This section is a dedicated grab-bag of horrors I’ve heard from other (anonymous) people. I’ll expand it as I hear new ones.

I know someone who feared that any given moment was a dream/memory/simulation.

I know someone who dreaded the prospect that aliens have been among us for a long time and the consequent discovery that reality had been a lie.

The good outweighs the bad, it’s better to never have loved than to have loved and lost. Life is the gradual accumulation of damage and hurt.

We live in a neutral universe beyond the reach of God, where immense horrors can occur for trivial reasons.

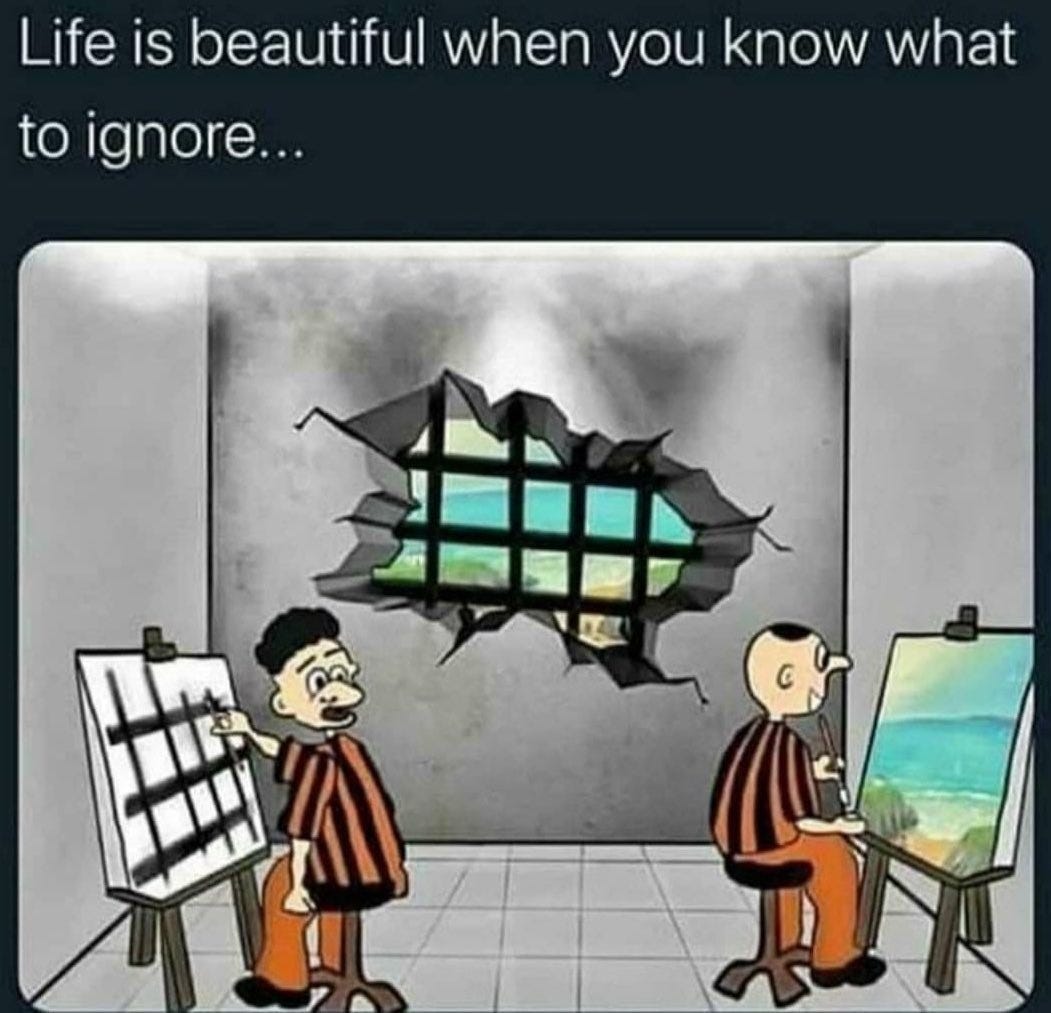

Solution 1: See No Evil 🙈

Back by popular demand, a fan favorite: just ignore it! La-la-la I can’t hear you! Shove the Horrors back into Pandora’s box. Sweep ’em under the rug. You can’t get served if you don’t answer the door. Don’t stare the basilisk in the eye. You get it.

People who perceive their world accurately are more likely to be clinically depressed. Those with delusional positivity tend to have better life-outcomes.

How to accomplish such a feat of blindness? One approach is the Dory Method: just keep swimming. Due to their subtlety, the Horrors prove most indsidious when you’re moving slow enough to fixate on them. A well-traveled path grows no weeds. If you fill your days with work and challenges, the Horrors will struggle to rear their ugly head. The Horrors are like tinnitus: omnipresent, but most audible in a quiet environment.

Even at death’s door, you can mask your horror by raging against the dying of the light. You can go out with a bang instead of a whimper: “Shoot, coward! You are only going to kill a man.” Screaming over your own tinnitus.

Other levers at your disposal include narratives and metaphors to temper the Horrors. If you focus on your tinnitus, it can grow deafening; if you craft scary stories in which life is a curse and existence is suffering, the Horrors can grow unbearable. “You’re not responsible for your first thought, but you are responsible for your second,” and you can manage your response to the Horrors. Monty Python reminds us to always look on the bright side of life.

Sometimes when I get depressed, I fall into the trap of thinking, “Oh yeah. This is how it is. The depressing elements in life are always present, even in the happy moments.” And by extension, efforts at happiness come to resemble “distractions.” The Good is just lipstick on the hog of Bad. I’ll admit, you can avoid the Horrors by distraction, but this critique presumes that the Horrors are somehow truer than the good: sure, you can outrun your demons, but maybe you just like running! The Horrors are a current that runs through life—they are existential—but that doesn’t make them fundamental to the Good. Maybe the Good is what is fundamental, and it is the Horrors that are the distraction. The two co-exist in parallel, and you can choose to empower either.

Solution 2: Explore the Evil

“I always felt that what is scary is actually hearing someone tell you what they think they see. That sense of invisibility makes things a lot scarier, since your imagination tends to fill in the gaps. So a character can be staring into the darkness behind a door and you just see the fright on their face. I think that’s scarier than showing you what’s behind the door.”

— James Wan, Horror Director

When hearing about someone’s death, I think there’s a natural impulse to ask how it happened. There’s this morbid curiosity: you want to stare the evil in the face. Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t. You’re allowed to arm yourself with a flashlight and go poking around in the basement. Maybe the only way out is through.

Solution 3: Gallows Humor

“After all, it is we ourselves who call this a funny war. Why not? I should imagine that no one would deny us the right to call it that if we please, since it is we who are sacrificing ourselves, not those others who think our epithet immoral. Surely I have the right to joke about my death if joking about it gives me pleasure . . . I have every right to my joke; for in this moment I am fully conscious of what I am doing. I accept death.”

— Antoine de Saint-Exupery, Flight to Arras

I have lots more to say about absurdism, but for now it suffices to say that something about scrounging for meaning in an indifferent universe is… funny? Consider Mr. Meeseeks from Rick and Morty: he appears like a genie at the push of a button and poofs out of existence upon completion of his task. His pleas strike me as extremely dark:

Meeseeks don’t usually have to exist this long. It’s getting weird . . . I can’t take it anymore. I just want to die! . . . Meeseeks are not born into this world fumbling for meaning, Jerry! We are created to serve a singular purpose for which we will go to any lengths to fulfill! Existence is pain to a Meeseeks, Jerry. And we will do anything to alleviate that pain.

But also it’s funny.

Contrapoints nails the tension and consonance between comedy and the Horrors in her discussion of The Darkness. (Interestingly, this is the same term that Bill Zeller uses in his suicide note to describe his depression.)

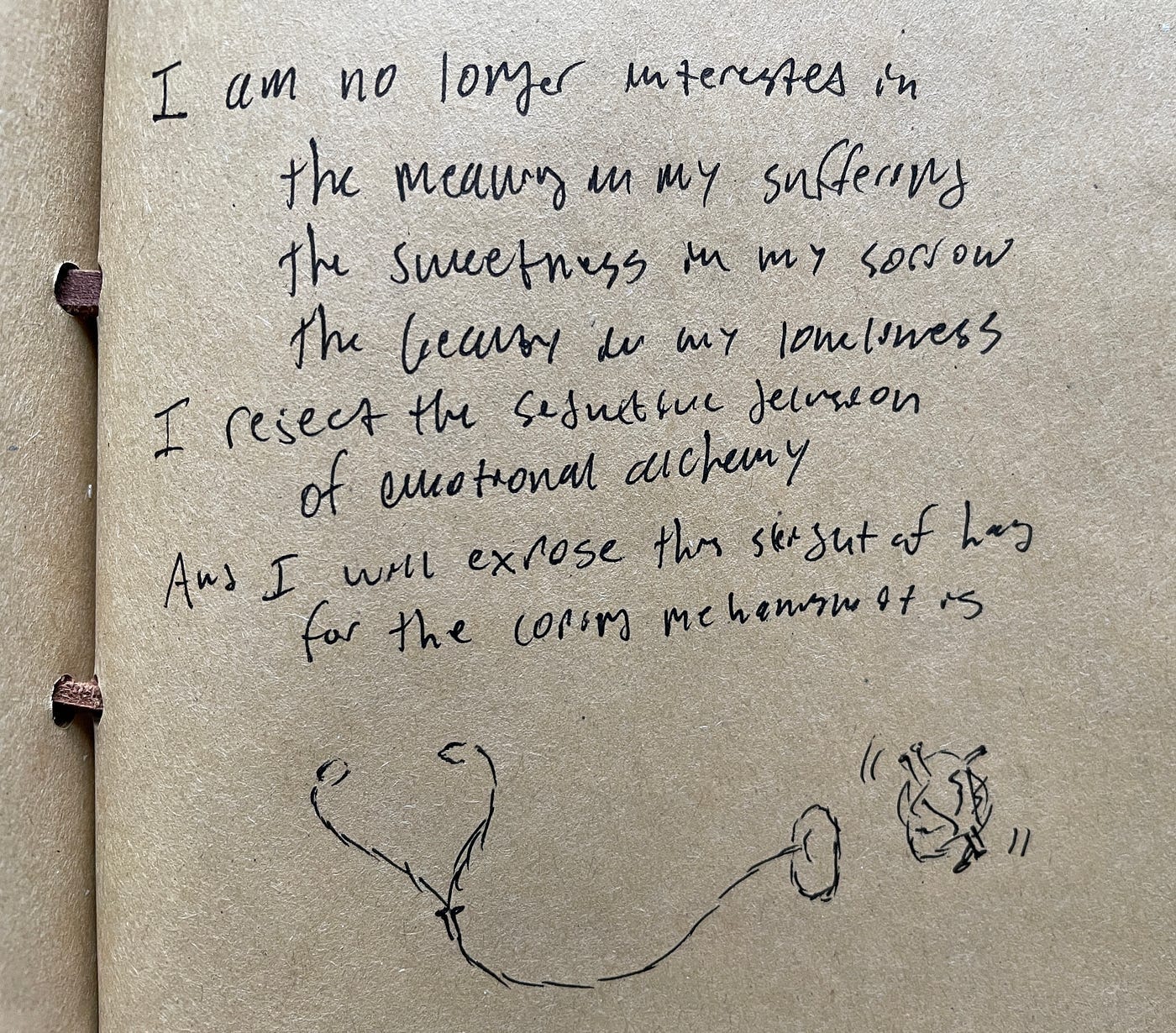

The comedic approach is not as disingenuous as Solution 1 but nonethelss might lack something in authenticity? Enough said, here are the poems.

This is from the Summer. I include it to illustrate the nature of this critique of absurdism: we might append “the humor in my horrors” to the list.

Solution 4: Counterbalance with the Glories

“All the glory that the Lord has made, and the complications you could do without, when I kissed you on the mouth . . . All the glory when you ran outside, with your shirt tucked in and your shoes untied, and you told me not to follow you.”

— Sufjan Stevens, “Casimir Pulaski Day”

My solution of choice, rather than denying, exploring, or laughing, counters with a force equal and opposite to the Horrors. In existential uncertainty, the Glories are their equals. But the Glories pull in the opposite direction of fear (as with humor, it’s unclear to me that there is an “anti-fear”, but we can certainly reduce fear to 0 and harbor attitudes toward that safety).7 Where the Horrors are scary, the Glories are wonderful; their experience is positively valenced.

Sufjan Stevens nails this (duh). When you’re dying of cancer but you can’t help falling in love, so you run outside half-dressed in the middle of winter, that’s glorious.

I saw this experimental mushroom play on a farm in Portland (I know), in which the mushroom-actors pushed through the soil into the air, going “Boop! Boop, Boop, Boop!” And just like that, I remembered, “Oh yeah. Being an accident of nature is weird, but what a tremendous privilege it is to get to be a little guy in this world! Boop, Boop, Boop!” This sentiment underscores that the Glories can be subtle like the Horrors: you might even glory in your daily tasks and feel grateful for your simple affairs.

Acknowledgements

“I get by with a little help from my friends.”

— The Beatles

Thanks to Sarena for posting the eponymous comic and talking about this nonsense. Shoutout to Mia and Jackson, the friends mentioned above. Mad props to Emily for mentioning comfort with impermanence when I was young. Much love to Andres for aiding me through some Horrors, Michael for giving me the courage to examine them, and Jamie for his peerless conversation. Thanks to Ariel for the Contrapoints video, Mariko for the Michael Singer quote, and my dad for assorted quips and bits sprinkled throughout. I also appreciate Mr. Bryant for showing our class this E. E. Cummings poem, whose levity belies its sinister conclusion, an evil that is difficult to pin down.

Appendix

Horror References

“A drink / For the horror that I’m in / For the good guys, and the bad guys / For the monsters that I’ve been” — My Chemical Romance, “Sleep”

Aaron Bergman thinks the Horrors are so horrifying that people can’t really conceive of them, at least not for long.

Unspeakability

“He took her hands, but realized once again the futility of words . . . Here words gradually lost the guarantee they were assured by our humanity.” — Antoine de Saint-Exupery, “Southern Mail”

“Scary stuff is invisible, Leah. Broken dreams, disappointment, achieving your greatest goal, having it all fall apart, and knowing that you’ll never climb any higher.” — Leslie Knope, “Parks and Recreation”

“I took a little journey to the unknown / And I’ve come back changed, I can feel it in my bones / I fucked with forces that our eyes can’t see / Now the darkness got a hold on me . . . There ain’t language for the things I’ve seen, yeah / And the truth is stranger than my own worst dreams . . . Follow me into the endless night / I can bring your fears to life” — Lord Huron, “Meet Me in the Woods”

“‘Snow in springtime, what is this?’ the Italian psycholinguist demanded in a tone that clearly signified charm and humor, but which to me seemed, like nearly everything he said, pregnant with the unspeakable sadness of the world.” — Elif Bateman, “The Idiot”

“Baby, I can’t speak {talk} about the hundred thousand darknesses that go around insisting they’re my heart” — Leonard Cohen, “The Flame”

Mortality and Impermanence

“For to wish to forget how much you loved someone — and then, to actually forget — can feel, at times, like the slaughter of a beautiful bird who chose, by nothing short of grace, to make a habitat of your heart. I hae heard that this pain can be converted, as it were, by accepting ‘the fundamental impermanence of all things.’ This acceptance bewilders me: sometimes it seems an act of will; at others, of surrender. Often I feel myself to be rocking between them (seasickness).” — Maggie Nelson, “Bluets”

“You can take a summer afternoon playing yard games with your family and make it last for years. Spend an eternity sitting by the fire with your loved ones, or tell a bedtime story to your kids that they’ll remember for eons. Grow a garden, and revel win its sweetness for a little while, before it all withers away, buried in snow and ash. Drop by to visit with friends, chatting about nothing particularly important. Call your parents. Go out and look at the stars while they’re still visible. Doodle away in the margins, and make art for its own sake, even though you know it won’t last more than a few thousand years. You can sit in a chair listening to music, while music still exists; you can curl up and read a good book while the language is still alive, while the words still have meaning.” — John Koenig, “The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows”

Loneliness

“Hell is other people.” — Jean-Paul Sartre

“I scare myself just thinking about you / I scare myself when I’m without you / I scare myself, the moment that you’re gone / I scare myself when I let my thoughts run” — Dan Hicks, “I Scare Myself”

Evolution

“How strange it is to be anything at all” — Neutral Milk Hotel, “Aeroplane over the Sea”

“You’re probably wondering why I’m here / And so am I / So am I” — The Mothers of Invention, “You’re Probably Wondering Why I’m Here”

“I’m very sorry that you have to have a body, one that will hurt you, and be the subject of so much of your fear.” — AJJ, “Body Terror Song”

“Practice original seeing while looking upon yourself and your situation. What do you see?

I see bundles of proteins and lipids arranged in a giant colony of cells, their lives given over to the implementation of a wet protein computer that thinks it's a person.

I see fractal patterns that arise on precisely the right sort of planet when you pour sunlight into it for a billion years.

I see wiggles in the Sun's wake that struggle to understand the universe. Incomprehensibly large constructs made of atoms, which are unnoticeably small on the scale of galaxies.

Look at us, the first species among the animals that can figure out what the stars are, yet still tightly bound to impulse and social pressure. (Notice how silly it is, monkeys acting all serious and wise as they try to affect the course of history.)” — Nate Soares, “Self Compassion”

I feel a little called out by this one:

Little Shop of Horrors

“But it wasn’t a dream — it was a place. And you — and you — and you — and you were there.” — Dorothy, “The Wizard of Oz”

“And this is the whole shabby secret: to some men, the sight of an achievement is a reproach, a reminder that their own lives are irrational and that there is no loophole, no escape from reason and reality.” — Ayn Rand, “Return of the Primitive”

Gender dysphoria?

See No Evil

Some say they're going to a place called glory / And I ain't saying it ain't a fact / But I've heard that I'm on the road to purgatory / And I don't like the sound of that / I believe in love and I live my life accordingly / But I choose to let the mystery be” — Iris DeMent, “Let the Mystery Be”

Explore the Evil

“There's a certain type of darkness in the world that most people simply cannot to see. . . When seeing that the world is broken, people reflexively feel a need to explain. . . This is the type of darkness in the world that most people cannot see: they cannot see a world that is unacceptable. Upon noticing that the world is broken, they reflexively list reasons why it is still tolerable. Even cynicism, I think, can fill this role: I often read cynicism as an attempt to explain a world full of callous neglect and casual cruelty, in a framework that makes neglect and cruelty seem natural and expected (and therefore tolerable).” — Nate Soares, “See the Dark World”

“[W]hen you try to minimize your own pain you’re doing yourself a disservice. Don’t do that. The truth is that it hurts because it’s real. It hurts because it mattered.” — John Green

“It turns out that the life of protecting yourself from your problem becomes a perfect reflection of the problem itself. You didn’t solve anything. If you don’t solve the root cause of the problem, but instead, attempt to protect yourself from the problem, it ends up running your life. You end up so psychologically fixated on the problem that you can’t see the forest for the trees. You actually feel that because you’ve minimized the pain of the problem, you’ve solved the problem. But it is not solved. All you did was devote your life to aavoiding it. It is now the center of your universe. It’s all there is . . . [Y]ou don’t want the weakest part of you running your life. You want to be free of this. You want to talk to people because you find them interesting, not because you’re lonely. You want to have relationships with people because you genuinely like them, not because you need for them to like you. You want to love because you truly love, not because you need to avoid your inner problems.” — Michael Singer, “The Untethered Soul”

“And for Geneviève these visits were the happiest moments of the day. Not that he consoled her—he said nothing—but because, when he was present, the little child’s body was precisely weighed and judged. Because everything serious, dark, unhealthy was clearly defined. What protection in this battle against the shadows! . . . [S]he uttered the word everyone was carefully side-stepping — death . . . She looked them straight in the eyes.” — Antoine de Saint-Exupery, “Southern Mail”

“It’s the heart afraid of breaking / That never learns to dance / It’s the dream afraid of waking / That never takes the chance / It’s the one who won’t be taken / Who cannot seem to give / And the soul afraid of dyin’ / That never learns to live” — Bette Midler, “The Rose”

“Right now you may not want to feel anything. Perhaps you never wished to feel anything . . . In your place, if there is pain, nurse it. And if there is a flame, don’t snuff it out. Don’t be brutal with it. We rip out so much of ourselves to be cured of things faster, that we go bankrupt by the age of thirty . . . But to make yourself feel nothing so as not to feel anything — what a waste! . . . Right now there’s sorrow. Pain. Don’t kill it and with it the joy you’ve felt.” — Professor Perlman, “Call Me by Your Name”

“In this world of wonders there are things a man must see

There are trials he must know and there are troubles he must meet

He must stare in the eyes of evil and know that he is free” — Justin Townes Earle, “Wanderin’”“Yet he continued to return to his core principle: that, in every situation, knowledge was better than ignorance.” — Haruki Murakami, “Men Without Women”

“‘Don’t look away, look right at it,’ someone whispered in his ear. ‘This is what your heart looks like.’” — Haruki Murakami, “Men Without Women”

“And if you are lucky enough to feel sad, well, savor it while it lasts—if only because it means that you care about something in this world enough to let it under your skin.” — John Koenig, “The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows”

“You almost make it seem like something nice / The way you take your bad news and you pour it over ice / That's a kindness that I don't appreciate / Because I like to take my sorrow straight.” — Iris DeMent

“He knows that once men are caught up in an event they cease to be afraid. Only the unknown frightens men. But once a man has faced the unknown, that terror becomes the known.” — Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, “Wind, Sand and Stars”

“If you can really allow yourself to feel it, your sadness doesn’t have to be so scary . . . You wouldn’t feel it if you didn’t have this immense care — and so you can see your own love through the lens of the sadness, which is a beautiful thing.” — Adrianne Lenker

“. . . mystery alone is at the root of fear. We must do away with mystery. Men who have gone down into the pit of darkness must come up and say—there’s nothing in it!” — Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, “Night Flight”

Gallows Humor

“We talk until we think we might just kill ourselves / But then we laugh until it disappears” — Phoebe Bridgers, “Funeral”

“Life would be tragic if it weren’t funny.” — Stephen Hawking

“We’re here because we’re here because we’re here because we’re here” — WWI Song

“Here are a few ways noticing absurdity can help . . . It can help us rest and step back a bit — noticing the absurdity of it all can make the things we work on feel strange to think about, even hilariously strange. That can help create some distance, and allow us to rest, or enjoy life when we’re not working on the absurd things. “I think that’s enough of working-out-what-the-world’s-biggest-problem-is-with-my-two-college-friends-in-college for one evening. UNSURPRISINGLY, I don’t think we’ll solve that before the end of the week”. — On Absurdity and Effective Altruism, Base Rates

The Glories

“[D]eliver us from evil. For thine is the kingdom and the power,

and the glory forever. Amen.” — The Lord’s Prayer“But if you could / Do you think you would trade it all? / All the pain and suffering? / Ah, but then you’d have miss / The beauty of the light upon this earth / And the sweetness of the leaving” — k.d. lang

“And every single breath we drew was Hallelujah” — Leonard Cohen

“There’s darkness in this life, but the brighter side we also may view.” — Uncle Tupelo, “Flatness”

“There is grandeur in this view.” — Charles Darwin

I learned today (3/30/24) that Richard Wright’s Black Boy has a section called “The Horror and the Glory.” I read the book in high school, so maybe that subconsciously influenced my choice of title.

The last two chapters, Smallness and Absurdity, evaded a blog post like this, but I decided to compose this one for various uninteresting reasons.

The other two are how to access God and how to answer the problem of evil.

Importantly, 40% of respondents led net-happy lives and 44% would live their lives again, which seems more consistent than the negative results. The remaining respondents were “neutral.” The survey was not representative.

See Midnight Gospel, “Turtles of the Eclipse” for a masterclass in the history of these norms.

See this Scott Alexander article for a historical example of people destroying the books they wrote.

See Midnight Gospel’s Mirror Man for more mirror content.

This point raises some complications for the interpretation of the life vs death twitter poll. If fear ≥ 0 and death = 0, then life is obviously going to contain more fear than death. I think the better interpretation is to compare the fear of dying against the subset of fears that are not about dying.