The following post was originally submitted to Astral Codex Ten’s 2024 book review contest. It is reproduced below with minor edits. This year’s rules included a special provision:

In past years, most reviews have been nonfiction on technical topics. To keep things interesting, I’m going to try some affirmative action this time (sorry, Supreme Court). ~25% of finalist slots will be reserved for books from nontraditional categories - fiction, poetry, and books from before 1900 are the ones I can think of right now, but feel free to try other nontraditional books.

Diversity Statement

Fish are very diverse animals and can be categorised in many ways.

— Wikipedia, Diversity of Fish

Is this book a work of fiction, perhaps one published before 1900? Well, no, it’s a work of fishin’ nonfiction. Is the book at least on an unusual topic? Metaphysics, perhaps? Er, no, it’s mostly about metafishics science—but it’s not like other nonfiction science books, I swear! Why Fish Don’t Exist is half-memoir, half biography, a frankenbook born of one woman’s monomaniacal insistence that a dead scientist possessed the only wisdom that could restore her to sanity. And it really makes an argument for why fish don’t exist! It just takes a while to get there. The book arguably belongs to a genre of its own, and it certainly breaks the mold of previous winners, thereby qualifying, I shamelessly claim, for preferential treatment in this here contest.

A Speck on a Speck on a Speck

Maybe tomorrow, the pills I couldn't swallow

They'll seem small, small, small, small, small

Sometimes I feel like a raindrop in the ocean

Fell from the sky, I melted into nothing

— Debbii Dawson, “Eulogy for Nobody”

Lulu Miller has an ancient problem. She was raised by a disabusive father, so as an adult she struggles with depression. The particular fiction of which her father disabused her was the idea that her life held some sort of cosmic importance. At age seven, she looked up at her dad to ask, “What’s the meaning of life?” And the cheeky bastard exclaimed, “Nothing!”

It felt like he had been waiting eagerly, for my whole life, for me to finally ask. He informed me that there is no meaning of life. There is no point. There is no God. No one watching you or caring in any way. There is no afterlife. No destiny. No plan. And don’t believe anyone who tells you there is. These are all things people dream up to comfort themselves against the scary feeling that none of this matters and you don’t matter.

Then he patted me on the head.

Now, I read these words, and my first thought is “based,” but Lulu Miller has a much harder time making peace with her cosmic importance because she has conflated smallness with insignificance. She grows from a suicidal teenager into a depressed adult, and she blames her woes on that persistent sense of insignificance her father instilled. In Lulu’s mind, insignificance becomes personified as Chaos, the agent of destruction responsible for our mortal woes.

Picture the person you love the most . . .

Chaos will crack them from the outside—with a falling branch, a speeding car, a bullet—or unravel them from the inside, with the mutiny of their very own cells. Chaos will rot your plants and kill your dog and rust your bike. It will decay your most precious memories, topple your favorite cities, wreck any sanctuary you can ever build.

It’s not if, it’s when. Chaos is the only sure thing in this world. The master that rules us all. My scientist father taught me early that there is no escaping the Second Law of Thermodynamics: entropy is only growing; it can never be diminished, no matter what we do.

Lulu’s depression may also have something to do with the matter of her ex-boyfriend of seven years, who left her after she cheated on him with some “bouncing blond girl.” But overcoming her lifelong crisis of meaning seems more tractable than winning back her ex, so Lulu sets out to solve the ancient problem.

Lulu harbors a fierce commitment to science: her parents were professors, and her father was a biochemist, so religious escapism is off the table. Where can one go to find meaningful connections in a secular community these days? LessWrong, of course! Indeed, nary a page expires without Lulu pondering some question that beloved forum has already pondered to death. Though she is as prime a specimen of a “proto-rat” as you will ever find, our poor Lulu is uninitiated in the art of rationality. Determined to recover her lost sense of meaning and unable to commiserate with the Sequences, Lulu investigates how others have reconciled themselves to the cold indifference of the universe.

Her first suspect is the thief who stole her meaning to begin with. Lulu’s father does not waste time on inconveniences like seatbelts, return addresses, or sleeves. That’s right—sleeves. One evening, he took a pair of scissors to his work shirts and liberated them of their sleeves, which would never again interfere with his experiments. Those experiments occasionally furnish Lulu’s dad with the organs of frogs, rays, and mice, which he takes home and fries. Oh, scientists and their snacks. He lives as though he has internalized the harsh truth that Lulu inherited, but awareness of his insignificance does not seem to compromise his ability to treat others well. And, unlike Lulu, the awareness does not seem to cost him his mental health.

What could be a grim reality has instead pumped his life full of vigor. Has made him live big and good. I have strived my whole life to follow in his nihilistic, clown-shoed footsteps. To stare our pointlessness in the face, and waddle along toward happiness because of it.

But I haven’t always been so good at it.

You don’t matter has often had a different effect on me.

Lulu tries to see things from her dad’s perspective. Over his desk, Darwin’s words assure that “there is grandeur in this view.” Lulu explains,

The quote comes from the last sentence of On the Origin of Species. It is Darwin’s sweet nothing, his apology for deflowering the world of its God, his promise that there is grandeur—if you look hard enough, you’ll find it. But sometimes it felt like an accusation. If you can’t see it, shame on you.

So Lulu can’t quite figure out what hidden principle animates her dad, despite his lowly place in the universe. Where he sees grandeur, Lulu finds only bleak insignificance

Rejecting her father’s example, Lulu does what anyone in that position is supposed to do: she moves to Chicago to spend an alarming amount of time obsessing over a strange older man, who may have committed murder. In Lulu’s case, that man is a fish taxonomist who died over 50 years before she was born, and his alleged victim was Jane Stanford, founder of the eponymous university.

So You Want to Be a Starr?

I made a deal with you

What I desire is man's red fire

To make my dream come true

Now, give me the secret, mancub

C'mon, clue me what to do

Give me the power of man's red flower

So I can be like you

— The Jungle Book, “I Wanna Be Like You”

Why does Lulu expect David Starr Jordan, of all people, to possess the secret wisdom she seeks? For one, he bore an uncanny resemblance to Lulu’s father. David, too, was not above tasting the subjects of his scientific inquiry. He wrote children’s books “that portrayed a claustrophobic world in which the characters could not escape the cold rules of our universe . . . There was no true magic, even for children. Just survival born of the creative harnessing of these cold, harsh rules.” In his writing for adults, David crusaded against “trying to believe what we know is not true.” His syllabus for a course on evolution declares, “Nature no respecter of persons . . . Tampering impossible . . . Her laws immutable . . . He who defies them wields a club of air.” Simply oozing with Rationality. Dedicating a day to the pessimism of evolution (a familiar topic), David even repeats Lulu’s father’s favorite line: “There is grandeur in this view.”

More importantly, David suffered the full wrath of Chaos, the demon haunting Lulu, and he set his jaw and persisted. David’s beloved older brother died to Typhus, his first wife died to pneumonia; his son died in a car accident, one daughter died to scarlet fever, another to an unnamed disease; his friend froze to death on a fishing expedition, one student went missing, another died to malaria; and nature destroyed his life’s work—twice.

The first of the two incidents occurred in 1883, when lightning sparked a fire that swept through David’s lab. Thousands of glass jars lined the walls, preserving their sacred contents.

Ethanol, though fabulous at stalling the universe’s attempts at decay, is friend to fire. The jars would have exploded like tiny bombs. Fish were vaporized. Unidentified creatures were incinerated, possibly never to be found again. Every last specimen was destroyed. And that wasn’t all. For years, David had been working on a secret document, a treasure map of sorts revealing never-before-seen branches of the tree of life. A huge and chandeliering chart made up of frenetic lines declaring insight, declaring evolutionary connections—completely torched.

To appreciate the magnitude of this loss, we must know a thing about taxonomists.

The first time a species is named, the specimen is placed in a very special jar, where it receives a very special honor. It is marked in the official scientific ledger as the sole maker of the species. In taxonomic lingo, any specimen is called a “type,” and, happily, this holy type happens to be called a “holotype.” . . .

One important rule about holotypes. If one is ever lost, you cannot simply swap a new specimen into the holy jar. No, that loss is honored, mourned, marked. The species line is forever tarnished, left without its maker. A new specimen will be chosen to serve as the physical representative of the species, but it is demoted to the lowly rank of “neotype.”

How did David respond to the tragic incineration of his holotypes? He set out again to replace his scaly trophies. David “did not consider the seeming futility of what he was trying to do—to make order in a world ruled by Chaos.” He did learn one lesson, though: “To publish at once.”

Perhaps even more devastating was the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, which destroyed his life’s work for a second time.

Hundreds of jars shattered against the floor. His fish specimens were mutilated by broken glass and fallen shelves. But worst of all were the names. Those carefully placed tin tags had been launched at random all over the ground. In some terrible act of Genesis in reverse, his thousands of meticulously named fish had transformed back into a heaping mass of the unknown.

But as he stood there in the wreckage, his life’s work eviscerated at his feet, this mustachioed scientist did something strange. He didn’t give up or despair. He did not heed what seemed to be the clear message of the quake: that in a world ruled by Chaos, any attempts at order are doomed to fail eventually. Instead, he rolled up his sleeves and scrambled around until he found, of all the weapons in the world, a sewing needle.

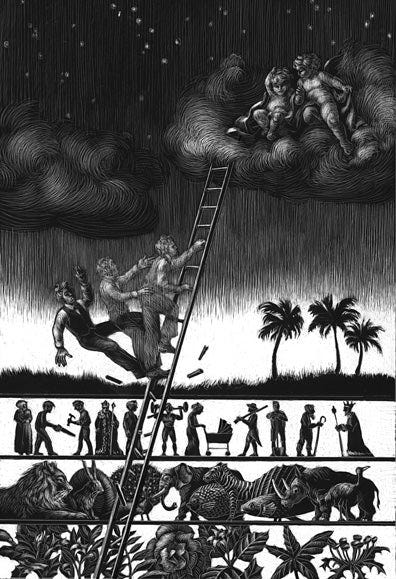

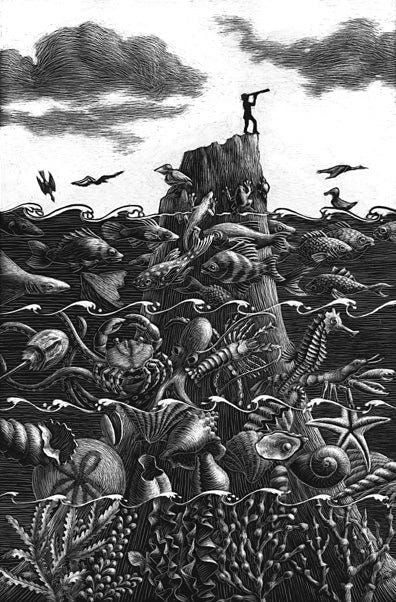

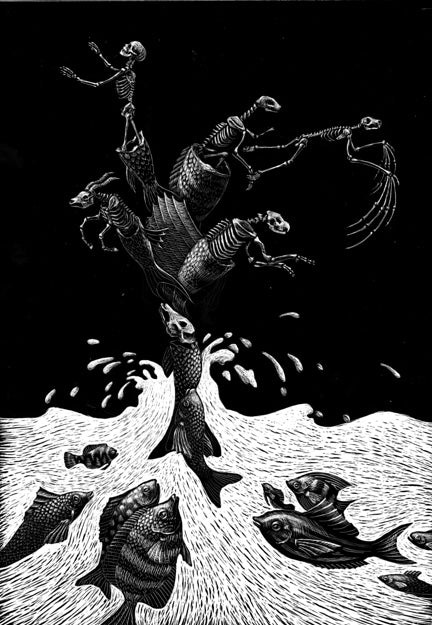

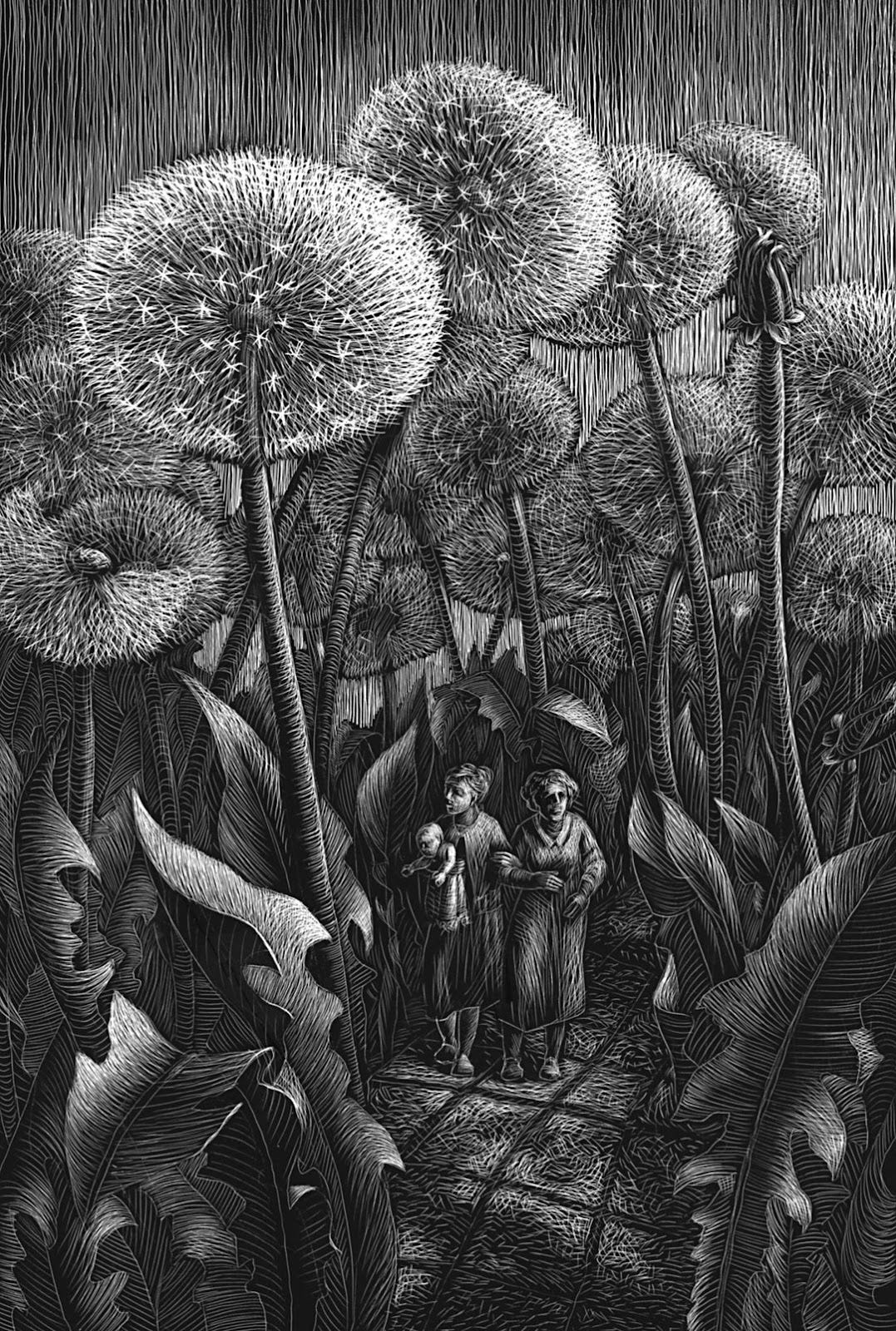

With the needle, David sewed those tin name tags directly to their corresponding fish, at least the ones he could identify in the wreckage. This act earned him Lulu’s admiration: “It was a small innovation with a defiant wish, that his work would now be protected against the onslaughts of Chaos, that his order would stand tall text time she struck.” It also earned each chapter of Lulu’s book a beautiful scratchboard engraving, which artist Kate Samworth primarily carved using a sewing needle. To explain his moxie, Lulu attributes some secret wisdom to David, wisdom that she might learn:

I wondered what it was that allowed him to keep plunging his sewing needle at Chaos, in spite of all the clear warnings that he would never prevail. I wondered if he had stumbled across some trick, some prescription for hope in an uncaring world. And because he was a scientist, I held on to the distant possibility that his justification for persistence, whatever it was, fit into my father’s worldview. Perhaps he had cracked something essential about how to have hope in a world of no promises, about how to carry forward on the darkest days.

So Lulu indulges her infatuation with David and purchases his two-volume memoir. Since a memoir is a review of a life, and Why Fish is effectively a review of David’s memoir, I think that makes this post a review of a review of a review

A Starr Is Born

With eyes that know the darkness in my soul . . .

Now, I understand

What you tried to say to meAnd how you suffered for your sanity

— Don McLean, “Vincent”

David was nearly born too late: by the time of his youth, the world had entered something of a taxonomy winter. The Age of Discovery had whetted the world’s appetite for exotic creatures, but globalization had already fed the hunger. Carl Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, had effectively shut the book on the topic with the publication of Systema Naturae in 1758—almost a hundred years before David was born. History might have frustrated David’s taxonomic destiny if it were not for the careers of two scientists.

The first was Charles Darwin, who published On the Origin of Species in 1859. Darwin argued that the familiar units of taxonomy (species, genus, family, etc.) were constructs that humans imposed on nature to make order out of chaos, not properties of nature itself. Even the intensional definition of species as a partition over animals based on whether they could produce viable offspring was riddled with exceptions.

The second was Swiss geologist and devout empiricist Louis Agassiz. Enacting his motto, “study nature, not books,” Agassiz would lock students in closets with animal corpses until they had extracted the scientific knowledge within. Eventually, Agassiz took a job at Harvard, and “he was troubled by what he found there. No digging around in the dirt, no students locked in closets with tiny rotting corpses. Just papers and tests and recitations regurgitating the beliefs printed in science books.”

The problem with memorizing scientific beliefs, Agassiz held, was that “science, generally, hates beliefs.” To justify Agassiz’ empiricism, Lulu gives some context that would make any rationalist’s heart sing:

As late as the 1850s, for example, many respectable scientists still believed in the idea of “spontaneous generation”—the belief that fleas and maggots could spring forth from particles of dust; a few decades before that, scientists believed in a magical substance called “phlogiston” that determined whether or not a material would burn; at that very moment, people had no way of protecting their loved ones against mysterious illnesses . . .

Illnesses like the ones that killed so many of the people close to David. To help the next generation catch the spark of empiricism, Agassiz started “a kind of summer camp for young naturalists.” History repeats itself. And of course, David Starr Jordan is selected to attend the camp on Penikese Island, off the coast of Massachusetts.

The Ladder of Nature

No one knows where the ladder goes

You're gonna lose what you love the most

You're not alone in anything

You're not unique in dying . . .

Don't hang around once the promise breaks

Or you'll be there when the next one's made

Kiss the feet of a charlatan

Some imagined freedom

— Bright Eyes, “The Ladder Song”

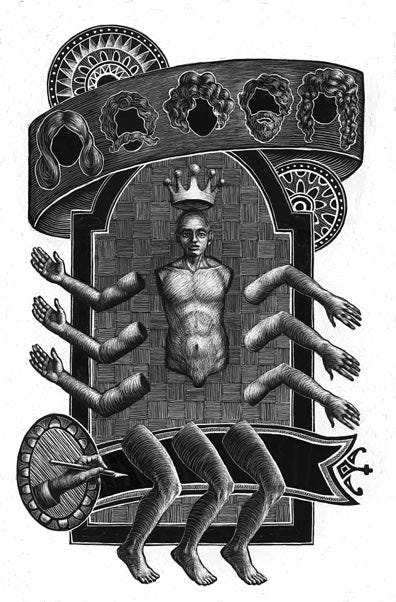

While David would come to owe a great intellectual debt to both men, Agassiz denied Darwin’s theory of evolution until the bitter end. Agassiz was too invested in a particular view of nature that was incompatible with Darwin’s. Born into a lineage of Protestant clergymen extending back seven generations, Agassiz treated nature as a kind of scripture. Before inviting his campers to pray, he taught that “a laboratory is a sanctuary where nothing profane should enter.” To study the species of the world was to “translat[e] into human language . . . the thoughts of the Creator.” Agassiz believed, and David agreed, that there existed an ordinal ranking of the animal kingdom according to the creatures’ favor in God’s eyes. Humans are superior to lizards, who outrank fish, and so on. Excavating the divine order revealed moral instructions that humans could follow to become more perfect, making taxonomy “missionary work of the highest order.”

To determine whether one species was more pious than another, Agassiz would invoke objective metrics like “the complication or simplicity of their structure” and “the character of their relations to the surrounding world.” Thus, humans are better than lizards and fish because we stand upright. Lizards are better than fish because they “bestow greater care upon their offspring.”

David picked up the habit. He crowned the eulachon “the most delicious of all fishes.” The silver maple was a “second-rate shade tree,” and the hagfish was a “pirate” with “bad habits.” What a great game! It was ELO Everything but for species. I recommend playing the next time you’re out for a walk. The squirrels gathering nuts for the winter? Gluttonous. The robins puffing their chests? Prideful. The sloths lazing around all day? Well, let me think on it. But I’m sure they’re no good! And humans above them all.

You can see why evolution would spoil the fun. If species were human constructs, they couldn’t be cleanly separated for the judging. If we had all descended from a common ancestor, how could we maintain our scientific anthropocentrism? Agassiz resolved the cognitive dissonance by denouncing Darwinism, but David, to his credit, reconciled the two perspectives. He wrote, “I went over to the evolutionists with the grace of a cat the boy ‘leads’ by its tail across the carpet!” But he maintained his belief that other species held warnings of the degradation that awaited humanity if we strayed too far from God.

He had taken Agassiz’s foggy idea of “degeneration,” mashed it up with Darwin’s theory of evolution, and ran with it. He saw the slimy hagfish as evidence that “bad habits” such as sloth or parasitism could make a species degenerate, devolve, or “change for the worse.” In a scientific paper, David proposed that the sea squirt, a sedentary sac of a filter feeder, had once been a higher fish but had “degraded” into its current form due to a combination of “idleness,” “inactivity and dependence.”

Textbook confirmation bias. Psychologists Lee Ross and Craig Anderson could have been describing David when they wrote,

Beliefs can survive potent logical or empirical challenges. They can survive and even be bolstered by evidence that most uncommitted observers would agree logically demands some weakening of such beliefs. They can even survive the total destruction of their original evidential bases.

You might think that David’s investment in this unscientific perspective despite contrary evidence would discourage Lulu from trying to learn from his example. Indeed, Lulu’s sacrilegious father had instilled the opposite lesson:

Never forget, as special as you might feel, you are no different than an ant. A bit bigger, maybe, but no more significant . . . except, do I see you aerating the soil? Do I see you feeding on timber to accelerate the process of decomposition? I do not. So you are arguably less significant to the planet than an ant.

Perhaps Lulu compartmentalizes their differences to justify her continued search through David’s life, in the same way that David compartmentalized his faith to justify his continued search through nature. In this hyperstitious exercise of confirmation bias, then, Lulu consecrates their sameness. Maybe David’s wisdom will generalize to Lulu’s problem, after all.

Lulu even approaches this understanding herself. Realizing that David was prone to narcissistic tendencies, she asks, “Was I doing exactly what I was beginning to suspect David of, twisting the facts to keep my worldview intact, to confirm my daddy’s belief that confidence corrupts?” But who can blame David for his confidence? He was a member of Homo sapiens, envy of the animal kingdom!

A Stanford Man

We’re no saviors if we can’t save our brothers

— The Wonder Years, “Cardinals”

At thirty-four years old, David was sworn in as president of Indiana University, making him the youngest university president in the US. A few years later, David’s reputation reached Leland and Jane Stanford, who were poaching talent for their new university. The enterprising taxonomist was quite a catch for the wealthy Californians, and David became the founding president of Stanford.

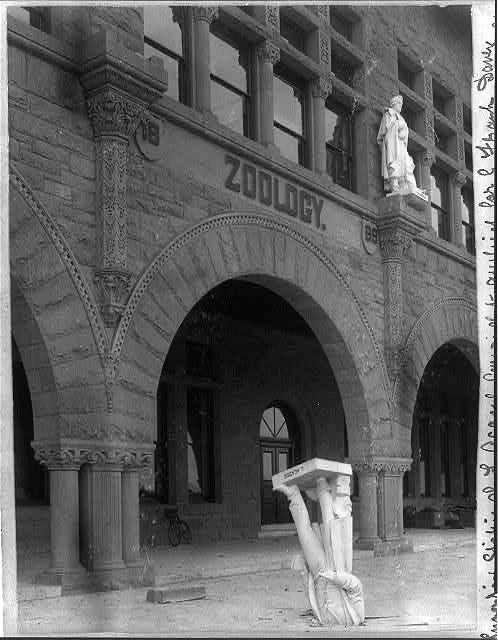

David’s first objective was to pack the science departments with his friends and former students. Then, he turned his attention to facilities. The Stanfords proposed, to David’s delight, a statue of Louis Agassiz for the new campus. The marble sentry was positioned over the entrance to the building that contained what David had restored of his fish collection since the first fire. David also commissioned the Hopkins Seaside Laboratory on Monterey Bay.

In 1917, the research lab relocated to a quieter spot, a 20-minute walk down the coast, where it stands today.

David and his second wife lived nearby, surrounded by a garden of plants from, in David’s words, “nearly every quarter of the globe.” In addition to cats and a Great Dane, the cottage was home to a parrot that spoke Spanish, a parrot that spoke Latin, and a monkey named Bob, who could be persuaded to ride the Great Dane like a horse.

David was asleep, surrounded by his family and their menagerie, when the 1906 earthquake devastated the San Francisco Bay Area. He ran through the turmoil of Stanford’s campus to his office, where carnage awaited him. Lulu writes, “Fish were everywhere. Glass was strewn all over the floor. Flounders bashed further flat by fallen stone. Eels severed by shelves. Blowfish popped by shards of glass.” And topping it all off:

David dispatched two trusted professors to keep hoses on the fish pile for two days and nights, while they waited for a shipment of ethanol. Then, his team sorted through the soggy hoard: the fish they recognized were returned to ethanol jars, this time with their names affixed directly to their flesh, and the jars were secured on their shelves, which were in turn reinforced and mounted. Still, a thousand specimens were not recovered. To appreciate the magnitude of the loss, we must also knowhing about names.

What’s an Anemone? That Fish We Collar Erodes

To exist, humanly, is to name the world, to change it.

— Paulo Freire, “Pedagogy of the Oppressed”

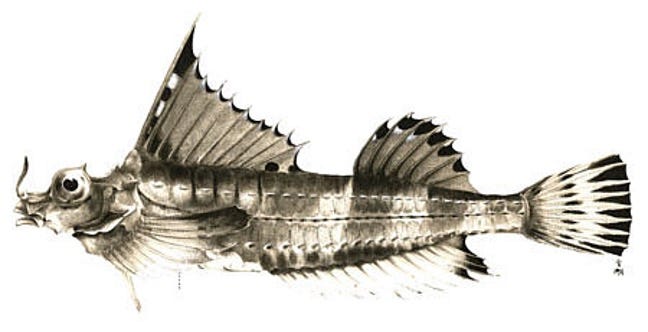

David was taxonomizing even as a boy. Before discovering the wonders of fish, David imposed order on the sky by learning the names of every star. For this reason, he chose “Starr” as his middle name. Naming has an addictive quality: it imposes (the illusion of) order on the natural world, which confers (the illusion of) control to the namer. For David, astronomy was just the gateway drug. Having conquered the heavens but still chasing the high of naming the natural world, David graduated to mapmaking, and then to herbology, which introduced him to the strong stuff: Latin names. It was not long before he was hooked on naming fish.

As David traveled the world with his team of ichthyologists, they came across fish unknown to western science. They occasionally intimidated fishermen into turning over their catches, and they often relied on the labor of local men, who probably could have told David what certain fish had been called for hundreds of years, but his team had other ideas.

The men get increasingly creative in their naming. They name ugly fishes after their enemies, pretty fishes after their friends. They are not shy to pay homage to their leader. A little flame of a fish plucked from Hawaiian waters gets the name Jordan’s wrasse, Cirrhilabrus jordani. There is Jordan’s snapper. Jordan’s grouper. Jordan’s sole. Lutjanus jordani. Mycteroperca jordani. Eopsetta jordani.

Off the coast of Japan in 1904, even David christened a fish with his name: Agonomalus jordani.

David took a name from nature; it seems only fair that David gave his name to nature, in return. It would have been more fun if he’d picked a starfish, though. As he encounters hardships and Chaos, naming the natural world remains an abiding source of Order for David.

There was always the relief of fish. That wide and watery world offering infinite comfort, better comfort, he was sure, than any booze or drug could provide. With each new fish, each new catch, each new name placed on a formerly unknown piece of the universe, came that impossibly intoxicating feeling. That sweet honey on the tongue. That hit of fantasized omnipotence. That lovely sensation of order. What a salve, a name.

So You Don’t Want to Be a Starr?

No need to worry 'cause everybody will die

— Awolnation, “Kill Your Heroes”

Predictably, David took the “degeneration” idea too far and got into eugenics. Like, really into eugenics, the forced-sterilization kind. He preached it to his students, published on the topic, and undertook speaking tours to spread the word. In one eugenics book, he wrote “An Arab proverb puts the matter bluntly: ‘Father a weed; mother a weed; do you expect daughter to be a saffron root?’” At a speaking engagement, David advised politicians that the “republic shall endure [only] as long as the human harvest is good.”

Confronted with this ugly history, Lulu loses interest in fashioning herself after David Starr Jordan. Where did her fallen hero go so wrong? David’s obsession with ranking species was always suspect, especially after he smuggled the habit through his transition to Darwinism. It was a foregone conclusion that, no matter what wonders David pulled from the water, humans would remain secure at the top of the natural hierarchy. Lulu begins to see this conceit as symptomatic of a deeper narcissism festering in David’s psyche. Plus, there was that thing where he might have murdered Jane Stanford. Maybe his secret for overcoming tragedy after tragedy was just an optimistic disposition and an inflated ego. Acknowledging David’s hateful ideology and the self-delusions that fueled it breaks the spell David held over Lulu. She could overlook some frivolous musings on Lizards Versus Fish, but she could not compartmentalize away the fundamental rifts she had exposed between herself and this dead scientist.

Now set on denouncing the folly of David’s approach to science, Lulu is met with sweet vindication. It turns out that fish don’t exist. Therefore, reasons Lulu, his life’s work was built atop a rotten foundation. No wonder he became mired in eugenics!

Let me explain the fish thing. In the 1980s, the cladists were ascendant in taxonomy. To untangle the branches of the evolutionary tree, taxonomists need to measure the evolutionary similarity of various species. Previously, they had been attempting this by brute force: enumerating species’ characteristics and counting the common traits. The cladists inaugurated a new paradigm. They would pin down some novel adaptation, say, the backbone, and trace it back to its genesis, collecting along the way every evolutionary branch that shared the novel feature. This process begot some counterintuitive conclusions, including that fish, as a distinct branch on the evolutionary tree, do not exist.

The cladists would illustrate their position like this:

They would begin by pointing to pictures of three animals. A cow. A salmon. A lungfish. Which of these things was not like the other? they would ask. Which creature was most distantly related from the group? And inevitably some poor, unsuspecting student would raise a hand and pick the cow. The cow is least like the fish. . . .

The cladists would remind you to focus on finding the shared evolutionary novelties. If you could, for just one moment, not be blinded by the cloak of scales, then you would begin to notice other, more revealing similarities. The lungfish and the cow, for instance—both have lung-like organs that allow them to breathe air, while the salmon does not. The lungfish and the cow both have an epiglottis (a small flap of skin that covers the windpipe). The salmon? Alas, epiglottis-less. And the lungfish’s heart is structured more like a cow’s than a salmon’s. The list goes on and on. Leading the students, finally, to the conclusion that the lungfish is more closely related to the cow than to the salmon.

And that’s when they would begin really revving their proverbial chain saws at the tree of life . . . [T]he cladists would say that once you accept this—that many of the fishy-looking creatures swimming in the water are more closely related to mammals than to each other—you begin to see a strange truth unfolding before your eyes. That “fish” as a sound evolutionary category is totally bunk. It would be like saying . . . “all the animals with red spots on them” are in the same category, “or all the mammals that are loud.” Fine, it’s a category you can make. But it’s scientifically meaningless. It tells you nothing about evolutionary relationships.

Still confused? Picture it another way. Imagine that for millennia we silly humans incorrectly believed that all creatures that lived on mountaintops were members of the same evolutionary group, called “mish.” The fish of the mountain. Mish. Okay. So mish includes mountain goats, and mountain toads, and mountain eagles, and mountain men—burly and bearded and enjoying their whiskey. Now let’s just pretend that, even though all these creatures are incredibly different from one another, they all happened to evolve a similar protective outerwear to survive at that altitude. Let’s imagine that outerwear is not scales but plaid. They are all plaid. Plaid eagles. Plaid toads. Plaid men. Such that they appear, what with their habitat (mountaintop) and their skin type (plaid), to be the same kind of creature. They are mish. We falsely believed them to be all of a kind.

We have done the same thing with fish—subjugated a world of nuance down into the word “fish.” . . .

The category of “fish” hides all of this. Hides nuance. Discounts intelligence. It gerrymanders close cousins away from us, creating a false sense of separation to preserve our spot at the top of an imaginary ladder . . .

No, the more scientifically logical thing to do is to admit that fish, all this time, have been a delusion. Fish don’t exist. The category “fish” doesn’t exist. That category of creature so precious to David, the one that he turned to in times of trouble, that he dedicated his life to seeing clearly, was never there at all.

So there you have it. Many species have become fish-like, despite disparate origins. It’s the familiar story of convergent evolution that has given rise to the world’s many-splendored crabs and trees.

Lulu considers this a damning indictment of David’s work. She admits that, if David had been alive for it, he probably would have come around to the cladist position. But she revels in the pain it would have caused the eugenicist: “His hurt, imagining him in some degree of anguish . . . it has a wonderful effect. It makes my skin prickle with the most forbidden of atheist fantasies. That somehow, out there, encoded in the cold math of Chaos, there is a sort of cosmic justice after all.”

Once again Lulu is guilty of the same crime as David, not the crime of confirmation bias but the crime of assuming orderly conduct. And again their common cognitive bias proves their similarity, two people displaying the same adaptation to the same harsh environment. But by this point, Lulu has identified the trait, a predilection for eugenics, that classes David in a past generation. No matter how similar they might seem, they belong to different branches of history, which insulates Lulu from relating to a eugenicist, but also cuts her off from the one person who offered hope of solace, more so than her own father.

The Way Out

Damn it, how will I ever get out of this labyrinth?

— Simón Bolívar

Lulu gave up on learning the grandeur-escape from her father, and she gives up on learning about order from David. In fact, David has soured her on the entire project. Making peace with insignificance requires imposing order on the world, and we know where that leads. So in a frenzy of disgust with eugenics, Lulu resigns herself to her suffering:

We don’t matter. This is the cold truth of the universe. We are specks, flickering in and out of existence, with no significance to the cosmos. To ignore this truth is, oddly enough, to behave exactly like David Starr Jordan, whose ridiculous belief in his own superiority allowed him to perpetrate such unthinkable violence. No, to be clear-eyed and Good was to concede with every breath, with every step, our insignificance. To say otherwise was to sin, to lie, to march oneself off toward delusion, madness, or worse.

But then, instead, Lulu decides that mattering is relative, and it is enough for her to matter to other people in her life, even if she does not matter to the universe. The end. Except, not quite, because despite the revelation, Lulu is still depressed.

At long last, I had found it, a retort to my father. We matter, we matter. In tangible, concrete ways human beings matter to this planet, to society, to one another . . . But there was still the problem of what I was driving toward, what we all were driving toward, in our cars with our headlights and our hope. That same empty horizon. I was still sure that our ruler was uncaring and cold, that waiting around the corner for each of us was precisely nothing. No promises. No refuge. No gleaming. No matter what we did or how much we mattered to one another.

But then she gives up on man-made categories entirely, which helps Lulu fall in love with her wife. The end for real. Upon abandoning categories,

I get, at long last, that thing I had been searching for: a mantra, a trick, a prescription for hope. I get the promise that there are good things in store. Not because I deserve them. Not because I worked for them. But because they are as much a part of Chaos as destruction and loss. Life, the flip side of death. Growth, of rot.

The best way of ensuring that you don’t miss them, these gifts, the trick that has helped me squint at the bleakness and see them more clearly, is to admit, with every breath, that you have no idea what you are looking at. To examine each object in the avalanche of Chaos with curiosity, with doubt. Is this storm a bummer? Maybe it’s a chance to get the streets to yourself, to be licked by raindrops, to reset. Is this party as boring as I assume it will be? Maybe there will be a friend waiting, with a cigarette in her mouth, by the back door of the dance floor, who will laugh with you for years to come, who will transmute your shame to belonging.

I find this whiplash conclusion, with its “at long lasts,” cliché and unsatisfying, but perhaps it is realistic. Through uncertainty, Lulu learns to marvel at the wonders of the world, including her wife, whom she addresses in the acknowledgements: “Spending time with you is the grandeur of my life.”

Taking the Long Way

All the rest is predictable

You can say you're the first to know

Bought a mantra to concentrate . . .

We'll welcome the new age

Covered in warrior paint

Lights from the jungle to the sky

See now a star is born

Looks just like a blood orange

Don't it just make you want to cry?

Precious friend of mine

Will I know when it's finally done?

This whole life is a hallucination

You're not alone in anything

You're not alone in trying to be

— Bright Eyes, “The Ladder Song”

The great tragedy of Why Fish, on a rationalist reading, is that for all Lulu’s proto-rat priming, it is the hairline fractures in her reasoning that cause her undoing. Casting her problem in existential terms privileged the question of how to reconcile science and significance, over a question like how to correct a neurochemical imbalance. The simplest explanation I see for her father’s satisfaction and David’s moxie is that they lucked into happy brains; Lulu could have focused directly on improving her welfare instead of seeking arcane wisdom. Instead, Lulu’s favored framing leads to a wild goose chase through David’s life story.

In the chase, Lulu is quick to dismiss David’s personal beliefs as pseudoscience without explaining how, exactly, they are incompatible with Darwinian evolution. She sees evidence of other unscientific beliefs everywhere. Then, giddy that fish do not inhabit a unified evolutionary branch, Lulu seems to suggest this fact fundamentally undermines David’s discoveries, which is not obvious to me. Finally, David’s advocacy for eugenics dirties Lulu’s image of him and everything he touches. His example becomes so irredeemably compromised that she cannot sample the good parts of his life and leave the bad parts behind. Thus, Lulu discards what might have actually been David’s secret wisdom: the power of names.

When I give up the fish, I get a skeleton key . . . To turn the key all you have to do . . . is stay wary of words. If fish don’t exist, what else do we have wrong? Slow dawning for me, a scientist’s daughter, but when I give up the fish, I realize that science itself is flawed. Not the beacon toward truth I had always thought it was, but a blunt tool that can wreak a lot of havoc along the way . . . That it is our life’s work to mistrust our measures. Especially those about moral and mental standing. To remember that behind every ruler there is a Ruler. To remember that a category is at best a proxy; at worst, a shackle.

She arrives at a healthy wariness toward science, but the insight comes at the cost of profound linguistic skepticism. Lulu could be forgiven for steering clear of words related to “fish,” that grievous misnomer, but in rejecting David’s example, Lulu also commits herself to a mistrust of all names, all categories. How much grief might she have been spared if she had heard the good news: the categories were made for man, not man for the categories.

Suppose you travel back in time to ancient Israel and try to explain to King Solomon that whales are a kind of mammal and not a kind of fish.

Your translator isn’t very good, so you pause to explain “fish” and “mammal” to Solomon. You tell him that fish is “the sort of thing herring, bass, and salmon are” and mammal is “the sort of thing cows, sheep, and pigs are”. Solomon tells you that your word “fish” is Hebrew dag and your word “mammal” is Hebrew behemah . . .

You try to explain that whales actually have tiny little hairs, too small to even see, just as cows and sheep and pigs have hair.

Solomon says oh God, you are so annoying, who the hell cares whether whales have tiny little hairs or not. In fact, the only thing Solomon cares about is whether responsibilities for his kingdom’s production of blubber and whale oil should go under his Ministry of Dag or Ministry of Behemah. The Ministry of Dag is based on the coast and has a lot of people who work on ships. The Ministry of Behemah has a strong presence inland and lots of people who hunt on horseback. So please (he continues) keep going about how whales have little tiny hairs . . .

There are facts of the matter on each individual point – whether a whale has fins, whether a whale lives in the ocean, whether a whale has tiny hairs, et cetera. But there is no fact of the matter on whether a whale is a fish. The argument is entirely semantic.

Permitting these sorts of ill-behaved categories would have offended Lulu’s understanding of science, sure, but her solution involved tempering her estimation of science, anyway. At least common categories could have retained some integrity in Lulu’s eyes. Though their boundaries are a bit arbitrary or subjective, Lulu has already accepted that species are defined by artificial boundaries around fuzzy clusters; it should be simple to extend the same understanding to other categories.

The first irony of Lulu’s resolution to her ancient problem is that meeting her wife seems to cure her angst. If she had focused on finding love from the beginning, maybe she could have reached the same happy ending while circumventing the entanglement with David altogether. Attributing her nuptial bliss to a suspicion of man-made categories sounds an awful lot like a confabulated explanation that conveniently redeems the untold hours she sunk into a wrongheaded search for wisdom.

The second irony is that Lulu Miller’s deliverance is marrying Grace Miller. Like David and the natural world, Lulu and her wife share names! If disgust toward David had not clouded Lulu’s search, maybe she would have identified this core lesson from his life and embraced the power of names, rather than renouncing words entirely. Names could have presented a shortcut to happiness, rather than an obstacle.

But no matter, Lulu got there eventually. She met a new partner, bestowed her name, and found some peace. Though Lulu ends up insisting upon her differences with David, one last similarity between them bears mentioning. By the end of David’s career, his team had discovered about a fifth of the 12,000 or so species known to humanity at the time. So for both the writer and the taxonomist, it turned out there were plenty of fish in the sea.

Acknowledgements

Fish are friends, not food.

— Bruce, the shark

Thank you to Michelle, who first told me about Why Fish, to Andrés, who called it a perfect book, to my neighbors, who were selling a yard sale copy for $1, and to Jeffrey, who supplied me with bountiful fish memes.