Introduction

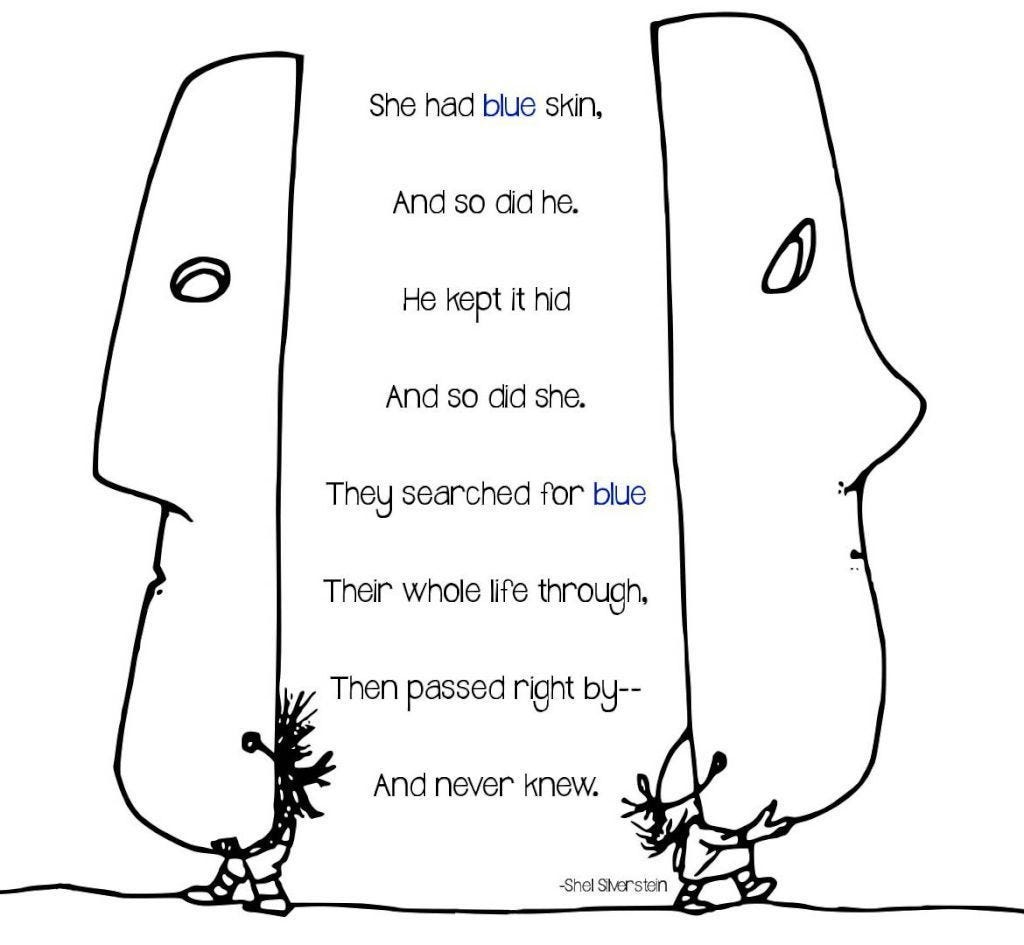

“Things are ‘real’ if they are real in the minds of at least a player.”

— Roberto Serrano, April 7, 2020

It took a minute to learn, but I eventually figured out that getting high, especially around other people, can make me pretty anxious. Wild. Some intrusive thoughts are easy to dismiss by the light of day: “I used to be such a happy kid, but now I’m irreparably damaged,” “I’ve probably said and done horrible things that I don’t remember while I was blackout drunk.” The attention of this post is directed at a particular flavor of paranoid thought that I’ve had much more difficulty rationalizing away, thoughts like “everyone hates me but pretends otherwise out of pity,” “everyone hates themselves but projects confidence to appear desirable.” More generally, that unkown miscommunications pervade my relationships.

January 25 of this year (2020) was one of the worst nights of my life. Playing Back to Back, a drinking game that tests how well you and your partner know each other, triggered the spiral. My partner, who was a good friend, answered prompts in ways that did not comport with my understanding of our relationship, and I thought our onlookers were ridiculing us. Responding to the question “Who is more considerate?”, we both indicated ourselves, and our circle of friends howled. I fled back to my room and layed down in the dark, but I rejoined my friends when they left for the club, where I spent most of my time in the bathroom. I got in a solid wall-punch before crashing that night.

That game of Back to Back possessed such sway over me because it confirmed an insidious idea that had been troubling me. That idea, which I term Relationship Skepticism (RelSkep), has occupied a prominent place in my recent thinking. The original purpose of this post was to explain RelSkep to my closest friends because it is important to me and bears implications for my relationships. Now I share it with you that you may derive some value from it. I designate the concept a basilisk (in the sense of an information hazard as used here, or a Thing Man Was Not Meant to Know) because my experience excavating it has resembled irreversibly dispelling a comfortable illusion. Having introduced the following thoughts to some friends, however, my impression is that others are resilient to the distress they have wrought on me. Please, then, forgive the post’s conspiratorial tone and, in the case of the discussion of falsifiability, perhaps explicitly conspiratorial content. I hope that you are not only unperturbed by this post, but that you think it’s nonsense, and you share your reasoning in the comments.

On the other hand, since I’ve started looking, I’ve found further instances of RelSkep attested in media and daily life. For some examples, consult the Appendix.

Suboptimal Equilibria

“And we’re standing in the hallway, both resolved to finally do this. We each have our guns drawn, but neither of us wants to shoot first. We could stay like this forever, we could stay like this and never leave.”

— The Future Kings of Nowhere, “Like a Staring Contest”

Suppose two people are meeting each other for the first time and each possesses the strategy set {Funny, Serious}. That is, each chooses whether they want to assume a funny or serious personality. The following payoff matrix captures this simple game:

The upshot is that both players benefit by playing the same strategy. Either both should be serious, or both should be funny, but both lose when one is funny and the other is serious—that’s just awkward.1 Though reductive, representing personality traits as strategy sets should seem reasonable because we all have different elements of our personalities that we emphasize in different contexts and relationships. As John Koenig writes, “Some of your friends are vastly different people when they’re one-on-one with each other, such that both would seem unrecognizable.” With some friends we’re more funny and with others we’re more serious, and those friends also adapt to their social environments. The question becomes, would we be better-off if our relationships were different?

Consider the variant of this game in which both players prefer a funny interaction to a serious one:

Both players are made best-off by playing funny, but if we impose incomplete information, this result becomes harder to obtain. Suppose that each player knows they personally would prefer a funny interaction, but is unsure about the other player’s preferences. Maybe the other player is a real stick-in-the-mud! Each player doesn’t want to risk cracking a joke to an unreceptive audience, so perhaps they play it safe by assuming a serious personality.2 The fear that both players could be stuck in the suboptimal equilibrium (Serious, Serious), when both would prefer the equilibrium (Funny, Funny) motivates the following formulation:

Weak RelSkep: Your relationships are in suboptimal equilibria.

But you disagree. You protest that communication solves: you can just ask your partner what they prefer. Barring that, you can get a feel for their preferences by testing out different personality traits and gauging their reactions.

Unfortunately, I don’t think it’s so simple. For one, there are penalties to communication: it can be off-putting to ask how someone feels about your relationship. Even then, there is no guarantee you will receive a truthful response because people face incentives to pretend the current state of the relationship is ideal and to withhold embarrassing or sensitive admissions about their preferences. The absence of communication yields pluralistic ignorance, in which everyone privately knows they would be happier under different circumstances, but doubts that others feel the same. (This is the concern that motivated the creation of Mojo Upgrade, a website that helps couples spice up their sex lives by circumventing the stigma of kinky sex to find shared interests.)

The more important response is that there are far more axes to personalities and relationships than just Funny-Serious, for example the “Big Five personality traits” or the four dimensions of the Myers-Briggs test. Moreover, these axes are not binary or even discrete as suggested in our contrived example, but rather continuous; e.g., everyone occupies some intermediate position on a Funny-Serious spectrum. In light of this complexity, there are far too many possible equilibria to feasibly exhaust them and make incremental personality adjustments in response to those tests. Moreover, the strength of the feedback from such tests is unclear: if I try to be a little funnier in one interaction, will I really gain sufficient information to improve our relationship? Feedback would be especially uninformative if the payoffs of the equilibria included many local optima because even if you could tell that one equilibrium was better or worse than its neighbor, you would probably have to assess every equilibrium to find the global maximum.

Apart from examining a game’s payoff matrix, another way to represent equilibria is by graphing the players’ “best response functions.” That is, for every possible move Player 2 could make, we plot the response that would make Player 1 best-off, and vice versa. Equilibria are found at the intersection of the curves because at these points the players are best-responding to each other. That is, neither can deviate to improve their position, which is the definition of an equilibrium. Addressing Weak RelSkep is daunting enough if players have simple best response functions like:

In this example we see two equilibria as we did in the case when players had only the binary strategy set {Funny, Serious}. Recall that our problem is determining whether the current equilibrium is the optimal one. This challenge becomes near-impossible when we consider less reductive response functions to better capture people’s idiosyncratic preferences:

Moreover, if the response functions coincided, there would be infinite equilibria in the Funny-Serious game. I think that multiplying this unwieldy proliferation of equilibria by the number of personality axes along which we relate to others endows Weak RelSkep with more legitimacy than it might command on first read. Even if there are very few suboptimal equilibria that prevail in the average relationship, it strikes me as very unlikely that any relationship is totally free of them.

For another example, consider the conversational equilibria “give-give” and “take-take.” Conversations work well when both participants both ask questions generously or both take the floor when they have something interesting to say. But conversations are easily monopolized when one person’s conversational style involves asking questions and the other’s involves taking the spotlight.

Ships in the Night: Perception & Interpretation

“You never know just how you look through other people’s eyes.”

— Butthole Surfers, “Pepper”

“O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us

To see oursels as ithers see us!

It wad frae mony a blunder free us,

An’ foolish notion”

— Robert Burns, “To A Louse, On Seeing One on a Lady’s Bonnet at Church”

Consider the possibility that the players in the Funny-Serious game agree that the relationship is in equilibrium but disagree about which equilibrium. For example, imagine that Player 1 believes they are playing Serious-Serious, but Player 2 is convinced they’re playing Funny-Funny. Then they would continue in this fashion, neither thinking that they could benefit by deviating. I don’t think this is all that far-fetched. Consider an introduction between Player 1, a conservative, and Player 2, a liberal. Player 2 recounts a recent news story about Trump, assuming Player 1 will catch on, but Player 1 treats the statement seriously and responds with some Fox News quote, which Player 2 in turn interprets as facetious. They go on this way, Player 1 assuming they are in the company of a fellow conservative and both are serious, Player 2 believing they are joking with another liberal. This example gives rise to the following definition:

Strong RelSkep: You are unaware that you and your partner disagree about some element(s) of your relationship.

First, note that Strong RelSkep generalizes Weak RelSkep, as the relationship’s equilibrium is one such element over which you might disagree. For example, you might be unaware that your partner prefers to be funny—you thought they preferred to be serious.

Second, note that your partner may or may not be aware of the disagreement (information may be asymmetric), but if the other person is aware, as a friend once said, they “will correct your misconceptions about them if you give them a chance. Some people aren’t really interested in being understood, but most people are.” On the other hand, the cases when your partner is also unaware of the disagreement are less tractable.

Since I began looking, I’ve found plenty of examples of this phenomenon. That game of Back to Back exposed an unknown disagreement in a friendship. In high school I had a whole conversation one time before my friend and I realized we’d been felicitously talking about totally different subjects. Recently at a Zoom meeting I was cracking up with another attendee; I thought we found the same thing funny, but it turned out she was laughing at something totally different. In a naturally occurring Gettier Case, my roommate told me once that her friend broke our door, and when I went to the bathroom I saw that it was hanging off its hinges. We talked about the door for a while before we realized that we’d been referencing different doors; the front door was in fact the one her friend broke, and the bathroom door happened to also have been in disrepair. I have many further examples, and I’m concerned that the ones I have discovered are just the tip of the iceberg: some of them I only became aware of by chance, and only just barely at that.

See this post on the Illusion of Transparency for empirics on misinterpretations of ambiguous statements. In a follow-up post, Yudkowsky writes, “I fell prey to a double illusion of transparency. First, I assumed that my words meant what I intended them to mean — that my listeners heard my intentions as though they were transparent. Second, when someone repeated back my sentences using slightly different word orderings, I assumed that what I heard was what they had intended to say. As if all words were transparent windows into thought, in both directions.”

Or, consider this example from Scott Alexander:

I’m about as introverted a person as you’re ever likely to meet — anyone more introverted than I am doesn’t communicate with anyone. All through elementary and middle school, I suspected that the other children were out to get me. They kept on grabbing me when I was busy with something and trying to drag me off to do some rough activity with them and their friends. When I protested, they counter-protested and told me I really needed to stop whatever I was doing and come join them. I figured they were bullies who were trying to annoy me, and found ways to hide from them and scare them off.

Eventually I realized that it was a double misunderstanding. They figured I must be like them, and the only thing keeping me from playing their fun games was that I was too shy. I figured they must be like me, and that the only reason they would interrupt a person who was obviously busy reading was that they wanted to annoy him.

Obviously, people have access to different information, but even when information is shared, I think miscommunication can still occur. Broadly, I think the two filters that give rise to this brand of miscommunication are perception and interpretation. On perception, remember wondering in childhood if everyone sees colors the same way you do, or whether your “red” is the color someone else calls “green?” The internet debate over whether the dress was blue and black or gold and white confirmed for me that my kindergarten musings about color perceptions were actually a bit founded. The yanny vs laurel debate extended this visual trickery to the aural realm.

Differences in interpretation are more pervasive. Consider, for example, this review of the movie Parasite, which claims that “the conventional interpretation is so obviously wrong that I cannot but think that it is anything but a collective gaslighting.” Like the film, the behavior of our loved ones is multievidential: it provides support for multiple interpretations.

As against Weak RelSkep, detractors can argue that communication renders Strong RelSkep unconcerning. Even if permissivism is true—i.e., people can legitimately interpret the same evidence in different ways—as long as people communicate about their different perceptions and interpretations, differing beliefs become common knowledge, and the relationship can move toward a state of agreement. If Romeo had received Friar Lawrence’s letter, a happier equilibrium would have obtained in the star-crossed lovers’ relationship. As above, however, exponents of Strong RelSkep can respond that penalties to communication and untruthful responses ultimately undermine communication’s solvency.

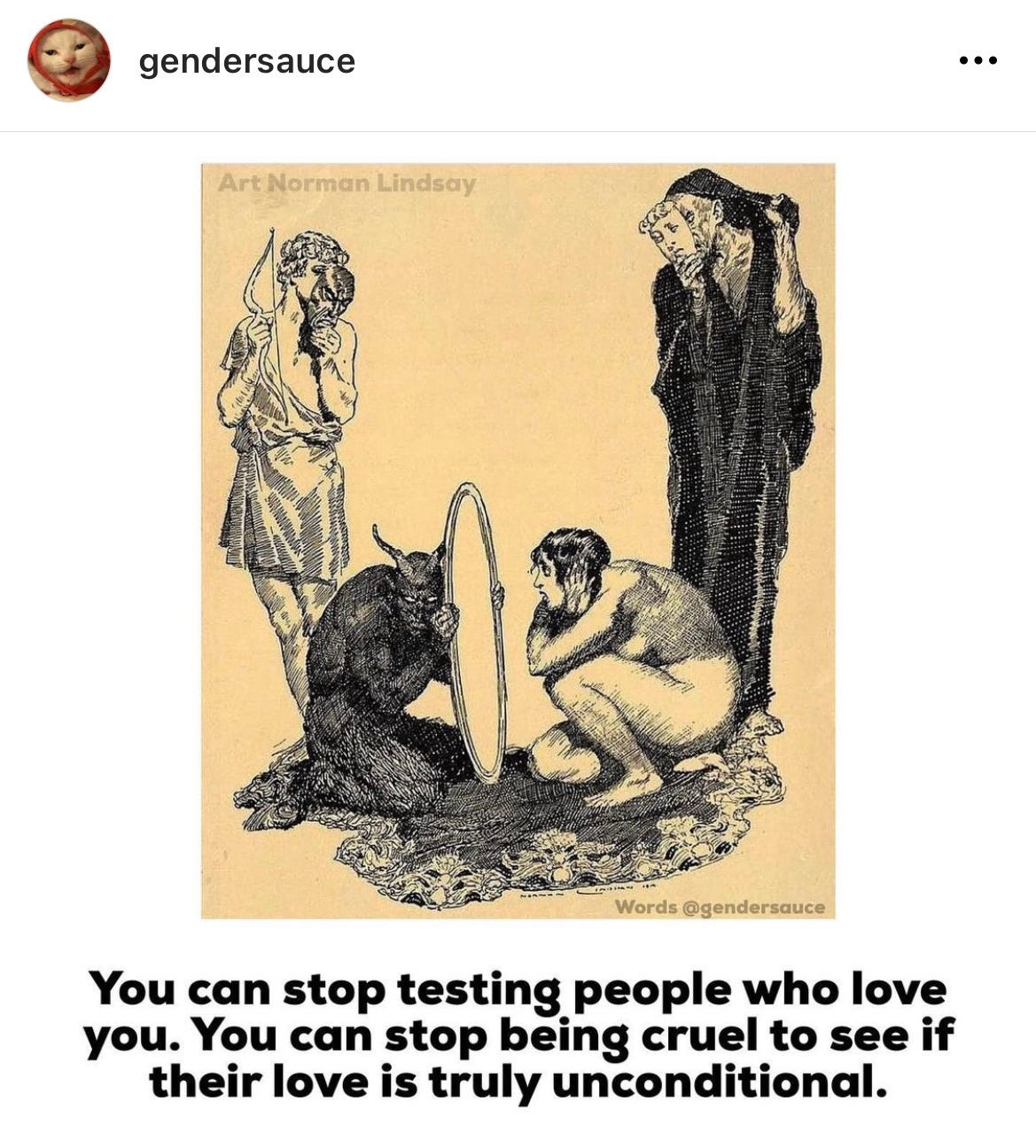

A more detailed example might be instructive here. Suppose you become concerned that your “friend” doesn’t actually care about you; they just instrumentalize your friendship to gain social capital or something. How would you go about coaxing this fear into the open? If you ask them directly, and they are in fact a loyal friend, they will certainly be hurt that you thought them capable of such deception and question what could have driven you to hold them in such low regard. In addition to this penalty for communication, if your friend is actually a clout-chasing snake, they aren’t likely to come clean just because you asked them directly.

Suppose you think that rather than communicating directly, you can test your hypothesis about the relationship. You might think that if you call your friend in the middle of the night, lying that your car broke down on the side of the road and you need a lift, a real friend would come to your rescue while a snake would decline. Again, this test carries a penalty: if your friend actually does pull themself from their blissful slumber to rescue you, then you’re the asshole. And again, it’s unclear how “truthful” they will be; that is, the low signal-to-noise ratio for your litmus test undermines its ability to distinguish a true friend from a fake friend. Even a fake friend might pick you up to stay in your good graces, and even a true friends might not pick you up for any number of reasons.

Apophenia & Confirmation Bias

“A man hears what he wants to hear and disregards the rest.”

— Simon & Garfunkel, “The Boxer”

The same checkerboard can host a game of chess or checkers, but in the Strong RelSkep case where one player tries to play chess against an opponent who sat down for a game of checkers, the discrepancy would quickly become apparent. Certainly, some interpersonal equilibria are like this. I’m not concerned that my friends are, for example, a hundred years older than I’d assumed because something would have tipped me off. The deeper concern stems from unknown disagreements that persist despite repeated interaction.

For one, I don’t think people often take the time to make an explicit mental model of their friends and relationships. If I ask someone to describe a certain friend of theirs, I frequently feel like they are reflecting on the question for the first time. False assumptions about others proliferate when we abstain from asking ourselves what we would have expected our friend to do in a given circumstance and contrasting this expectation with their realized behavior. If we don’t make predictions, we are probably indulging in pseudoscience. Paraphrasing Karl Popper, Hank Green says, “science disconfirms, pseudoscience confirms.”

Even if we do make an explicit mental model (“I believe my friend is introverted…should I update my model after seeing that keg stand?”), I still think this is insufficient to dispel many false assumptions. Maybe this applies more strongly to me than most people, but I strive to “imagine others complexly.” That means I try to refrain from reaching sweeping conclusions about someone on the basis of the limited and biased data I gather from our interactions. By definition, then, I’m loath to update the limited mental models that I do construct. This type of epistemic humility begets models of others that exhibit near-infinite explanatory power. Just as a bad person can do good things without you revising your belief that they are a bad person, so too can an introverted person do extroverted things or a funny person act serious. This malleable attitude toward others makes my beliefs about our relationships impervious to contrary evidence.

Even if the “imagining others complexly” motivation is only salient to me, I think there are reasons why everyone misimagines others or fails to recognize behavior that doesn’t align with their expectations. The first of these reasons is apophenia, the tendency to perceive patterns in random data. Even if your partner’s funniness was determined by a uniform probability distribution over the Funny-Serious continuum, you might still interpret their personality as, e.g., overall funny, or following a more complex pattern.

The second reason I have become more confident in the prevalence of Strong RelSkep is confirmation bias, the psychological phenomenon by which people search for, interpret, and recall information to confirm their prior beliefs. The whole Wikipedia article is worth a read, but a quote from psychologists Lee Ross and Craig Anderson nicely sums up the implication of this cognitive bias for our present undertaking:

[B]eliefs can survive potent logical or empirical challenges. They can survive and even be bolstered by evidence that most uncommitted observers would agree logically demands some weakening of such beliefs. They can even survive the total destruction of their original evidential bases.

Even if we’re not actively trying to imagine others complexly, I think we probably can’t help but interpret information in motivated ways. I know my parents are so desperate for good news about my sibling’s health that they pounce on any positive evidence as proof of progress and downplay contrary evidence as exceptional. For another example, consider the immense validity that people afford astrology.

Other psychological predispositions bias your interpretations, further distorting your understanding: “Anxiety is a bias towards processing information in a threat-related way . . . Depression is a bias towards processing self-related information in a negative way.” Loneliness involves a bias toward social rejection.

In light of these handicaps on perception and interpretation of others, the project of truly understanding each other begins to look a bit hopeless.

So What?

“We are let into a wonderful world, we meet one another here, greet each other — and wander together for a brief moment. Then we lose each other and disappear as suddenly and unreasonably as we arrived.”

— Jostein Gaarder, Sophie’s World

Note that if you buy Strong RelSkep, then for the same reasons, you implicitly accept that your prevailing understanding of your relationships is somewhat arbitrary. This realization provides fertile soil for the kind of paranoid alternative understandings mentioned in the introduction, and these depressing thoughts can prove just as sticky as the naive assumption of understanding that preceded exposure to Strong RelSkep.

A better response to Strong RelSkep than communication is a form of Occam’s Razor that runs: at any given time, our beliefs about others are the simplest ones or the beliefs made most likely by their observed behavior, so there’s no need to fret over our uncertainty. I hope the discussion in the previous section sufficiently troubles the idea that we form beliefs about others through rational Bayesian updates. Moreover, your previous assumptions might be far more complex than the alternatives that Strong RelSkep invites you to consider. But suppose otherwise. Even taking the argument at its best, we can still play ball over the link into disregarding Strong RelSkep.

I simply don’t think that Occam’s Razor applies here. The warrant behind the razor is that simpler theories are easier to test and falsify, not that simpler theories are a priori more likely to be true. The issue, then, is that most of the possibilities we might consider about the personalities of others and our relationships with them are not falsifiable! In science, this might be a blasphemous admission, but real people behave in messy ways that don’t follow immutable laws of nature. In fact, Karl Popper, himself, once said, “It is impossible to speak in such a way that you cannot be misunderstood.” The question then becomes, “So What?” Why should I care about the infinite array of motivations and personality traits that possibly animate my friends any more than I care about the infinite array of gods I might pray to?

Maybe you shouldn’t. Maybe you can be content as a relationship agnostic. But I think it does matter and possibly matters quite a bit. If Weak RelSkep is true, that would obviously matter because then we could improve our relationships and everyone would be better-off. Similarly, if Strong RelSkep is true, then miscommunication is more likely to interfere with our relationships. Most of the time, I think these miscommunications probably manifest in small ways, e.g., poor gift choices, and can be corrected. The more important impact flows from the tail risk of an error cascade in which an initial miscommunication triggers a spiral that terminates in the end of the relationship.

Other impacts of Strong RelSkep are more subtle. One is that it is demanding to simultaneously hold contradictory understandings of your friends. The cognitive load imposed by uncertainty between even binary types can be overwhelming, especially when considering a distressing possibility, for example when constantly evaluating your partner’s behavior in light of the question “Are they cheating on me or not?” Another reason is that ambiguity aversion is well-attested in behavioral economics: people don’t like not knowing the probabilities of events, which is a consequence of Strong (and Weak) RelSkep.

Windows and Mirrors

“Wanna be loved, not for who you think I am, nor what you want me to be. Could you love me for me?”

— Buju Banton, “Wanna Be Loved”

The final—and personally, most important—reason why Strong RelSkep matters is that it undermines what I see as the fundamental purpose of relationships: deeply knowing another person. Connecting with others is the only source of solace from the oppressive loneliness of existence. Only by understanding, empathizing, loving others can we escape the confines of our own lives. I’m sure I’m projecting a bit, but I think that if most people really considered what it would mean to not know their friends as well as they had assumed and to examine the range of alternative interpretations of their friends’ personalities that are compatible with their friends’ behavior, they would feel troubled, too.

Statistics teaches us that we face a tradeoff between confidence and accuracy: tighter confidence intervals require lower confidence levels. In approaching your relationships, you can determine your own balance with respect to this tradeoff. Maybe you prefer a model of your friends that prioritizes a high degree of confidence at the expense of accuracy, so you can say “I’m 99% sure they are somewhere between the funniest and least funny person I’ve ever met.” Regardless of your preference, the arguments above imply that you cannot have as much confidence or accuracy as you might have assumed because the space of possible personalities is enormous, communication is hard, and your cognitive biases have grossly interfered with past updates to your beliefs. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and presuming to deeply know your friends is an extraordinary claim in light of our cognitive biases and the overwhelming variety of human behavior, even from a single person.

Sealing the Can

“Uncertainty is the only certainty there is, and knowing how to live with insecurity is the only security.”

— John Allen Paulos

So we have stared at the basilisk, opened Pandora’s box, sniffed Manzoni’s can of shit. The question becomes, if the concern is a real one, what can we do about it? First, I like to affirm my agency by reminding myself that I am half of my friendships and therefore partially responsible for whatever equilibrium obtains in them. Like the ideomotion that is in fact responsible for the planchette’s seemingly autonomous movement over the ouija board, my actions shape the movement of my relationships. Second, I do think that communication is an important tool. Awareness of RelSkep at least allows for deeper interrogation of our friends, and through inquiry, we can converge on a narrower range of possible beliefs about our friends’ identities. Hopefully in doing so we can eliminate our most toxic fears about them. For example, try asking your friends how they think of your personality (e.g. 10% ambitious, 25% nerdy, etc…), and then asking them what they think you think of their personality.

Aside from this, though, I think we have two possible responses. The first is to disregard this post and continue as if you’d never encountered it. The second is to believe in the world you most prefer. Tell yourself that your friends love you. Learn to believe that they’re happy and love themselves. Pretend that they’re super similar to yourself if that’s what you want to be true. At least look for evidence to disconfirm the most toxic fears to the contrary.

Both approaches require a leap of faith to deny RelSkep and its implications for our relationships. Horrified, Kantians might argue that our moral obligation to not treat people as mere means demands that we not instrumentalize our friends as vehicles for imagination as though they were human lottery tickets. That we ought instead unrelentingly pursue truer understanding of the people who mean the most to us. I don’t personally find this compelling, but some of you might. My greater concern with these solutions is a pragmatic one: that we can’t fully delude ourselves into believing we figured out the One True Self of our friends, so even after attempting these suggestions, we will still have to contend with the loneliness of failing to deeply know other people. Even the most vivid imaginary friend falls short of a real person’s company.

Acknowledgements

“You are the truth I choose to bend myself around. I felt so awkwardly divided, you defined my lines somehow.”

— The Front Bottoms, “The Truth”

Thank you so much to my friends who have entertained these febrile thoughts over the past months. I am particularly grateful to Sandy for their thoughtful introduction to Kierkegaard’s qualitative leap, to Andrés for his counsel following the Back to Back night and statistical arguments following the publication of this piece, to my darling mother for her deep listening, to Jamie for his conversation and validation, to Albert for his grindstone arguments, and to Michael for his candor and encouragement. You may not remember these contributions, “even so, they have made me.”

Appendix

Here are some pieces of evidence that further support the commonality of RelSkep.

Accidental (Two-Way) Misunderstandings

Scott Alexander describes an encounter in which he believes he insulted a coworker and the coworker instead thinks they were just joking around.

If two people blink at the same time, they’ll never know it.

Community S4E8: Shirley and Annie have a conversation gloating about winning a competition that each believes herself to have won.

When I was coding an AI player for a game, I learned you could have two AIs play against each other on the same “board” while both believed they were playing different games.

The banana-bandana skit

People talk shit about each other behind their backs and smile to each other’s faces.

This train car/carriage joke

I’ve laughed with someone else, but when we try to talk about it, we realize we were laughing at different things.

Romeo and Juliet

I thought my friend was depressed and he thought I was tired! We were both fine…

Arrested Development S2E3: Two characters have a whole conversation where they’re referring to different people without realizing it.

Arrested Development S2E8: Same device

How I Met Your Mother S1E6: Two characters enter a relationship that each outwardly enjoys but secretly finds intolerable.

“Relationship chicken” in How I Met Your Mother: early in a relationship, both partners find themselves participating in activities they do not enjoy to avoid disappointing the other and to maintain the impression that you are exciting.

“anderance n. the awareness that your partner perceives the relationship from a totally different angle than you—spending years looking at a different face across the tale, listening for cues in a different voice—an odd reminder that no matter how much you have in common, you’re still in love with different people.” — John Koenig, The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows

“A man lays down a marker by mentioning something he knows, an opening bid in establishing his status. A woman acknowledges the man’s point, hoping that she will in turn be expected to share and a connection will be made. The man takes this as if it were offered by someone who thinks like him: a sign of submission to his higher status. And so on goes the mansplaining.” — The Economist

@kelseycookcomedy on TikTok describes a conversation in which she tries to express that her cat died, but her friend thinks their mutual friend died.

Intentional Misunderstandings

“Sometimes the truth is hidden in plain view… We believe in lies so we can relax for a little bit / We close our eyes so we can see what we want to see / Ignorance is bliss / We can miss what we want to miss” —Our Last Night, “Ignorance Is Bliss”

“She see what she want to see” — Childish Gambino, “Kids”

My old roommate believed she could tell what she wanted out of a relationship with someone within five minutes of meeting them. Maybe she has keen insight… or maybe she makes an assumption and builds a case for it over the course of the relationship.

Collective fictions like money or nations.

Multiple Meanings

30 Rock S6E8: Jack gets mugged during a phone call with Liz and tells his mugger “Let’s just get this over with.” Liz assumes the statement is directed at her.

Poe’s Law: Without a clear indicator of the author’s intent, every parody of extreme views can be mistaken by some readers for a sincere expression of the views being parodied.

“It is living with uncertainty — knowing on a gut level that there are flaws, they are serious and you have not found them — that is the difficult thing.” — Eliezer Yudkowsky

A couple times in my life, I’ve texted someone thinking I was contacting someone else. And proceeded to have a full conversation, including words that meant different things to the different addressees.

30 Rock S3E2: Jack has a conversation with two different people simultaneously.

30 Rock S5E15: Liz comes up with two interpretations of an experience; either it was authentic or orchestrated by her friends. She goes with her preferred explanation.

How I Met Your Mother S2E19: Lily’s grandmother describes a gift that she believes is a sewing machine but is in fact a sex toy. Despite the mistake, the description could have applied.

Simulation theory!

The meme in which your English teacher asserts that the curtains are blue to symbolize the narrator’s depression, etc. When in fact, they are simply blue.

That Spongebob episode where he thinks Mr Krabs is a robot

“Daisy isn’t really saying anything ‘meaningful,’ but because people search for meaning and order even in random information, we tend to notice and remember things that suggest that the program might actually be thinking.” — Exploratorium exhibit on Daisy the chatbot

“While people are fairly young and the musical composition of their lives is still in its opening bars, they can go about writing it together and exchange motifs (the way Tomas and Sabina exchanged the motif of the bowler hat), but if they meet when they are older, like Franz and Sabina, their musical compositions are more or less complete, and every motif, every object, every word means something different to each of them.” — Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

Confirmation Bias

Anxieties Sustained by Uncertainty

If two kids tell their parents that each is spending the night at the other’s house, then they are free to get up to no good.

What if you have a learning disability and no one has told you?

You’re worried that you’re annoying to your friend, but you don’t feel close enough to ask them, and maybe they would lie to you if you did.

How I Met Your Mother S3E8: Everyone learns what others don’t like about them, discovering flaws they weren’t aware of.

A friend tells you they’re a compulsive liar. You never would’ve known!

“maugry: adj. afraid that you’ve been mentally deranged all your life and everybody around you knows, but none of them mention it to you directly because they feel it’s not their place.” — John Koenig, The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows

We might have modeled this interaction such that both players prefer a Funny-Serious relationship without loss of generality; that is, for our purposes we would see the same results, but I continue with the above game in which both players prefer to match each other’s energy.

Game theory aficionados can recognize that including asymmetric penalties for anti-coordination would turn this game into stag-hunt.